¶ 1Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0Not only do objects change through their existence but they often have the capability of accumulating histories, so that the present significance of an object derives from the person or events to which it is connected.1

¶ 2Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0In the golden age of our existence, not only did we enjoy the light and heat around us, but we carefully stored away considerable portions. These we now freely render up to you again, thus giving you another proof that nothing is ever really lost—nothing is ever actually destroyed.2

¶ 5Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

The attack came from the north. Leading the advance was a column of North Korean tanks followed by two regiments of North Korean troops numbering nearly 5,000 soldiers. Opposing this force was a group of around 400 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 24th Infantry Division, 21st Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bradford Smith, a group nicknamed “Task Force Smith.” The group had arrived in Korea only five days earlier, on July 1, 1950. They were among the first U.S. troops to arrive in Korea, having left Japan, where they were stationed, in response to the United Nations Security Council’s decision to send military forces to contest North Korea’s recent invasion of its southern neighbor, the Republic of Korea, on June 25, 1950. Task Force Smith was positioned in the hills north of the town of Osan, with the purpose of halting or delaying the North Korean advance in order to buy time for more U.S. forces to arrive in Korea.

¶ 6Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Task Force Smith, however, was outmanned, had little combat experience, and was poorly equipped to battle a larger force with mechanized armor. The column of North Korean tanks swept through the first line of infantry defenses unscathed and continued down the main highway, where they encountered a small reconnaissance team of the 34th Regiment sent from battalion headquarters. This reconnaissance team attempted to destroy the tanks using their bazookas. One of these soldiers was Private First Class Kenneth Shadrick, from West Virginia. Also accompanying the team was Sergeant Charles Turnbull, an army combat photographer. No doubt spurred by the historic moment of that first day of engagement with an unknown enemy in an emerging conflict, Turnbull wanted photographs of the reconnaissance team as they fired their weapons, and Shadrick agreed to fire next. After firing from his foxhole, Shadrick rose up to assess his shot and was struck and killed by fire from the tank’s machine gun. Marguerite Higgins, the pioneer female war correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune, had witnessed the engagement from afar and was also present when Shadrick’s body was brought back to battalion headquarters. As she later wrote in her memoir,

¶ 7Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

I was talking to a Medical Corps sergeant when they brought in the body of Private Shadrick.… As they carefully laid his body down on the bare boards of the shack I noticed that his face still bore an expression of slight surprise. It was an expression I was to see often among the soldier dead. The prospect of death had probably seemed as unreal to Private Shadrick as the entire war still seemed to me.3

¶ 8Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

The stories that Higgins and other correspondents filed identified Kenneth Shadrick as the first reported American killed in action of what would come to be known as the Korean War.

¶ 11Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0Figure1. “A team mans a Bazooka at the Battle of Osan. Members of the 24th Infantry Division, first United States ground units to reach the front, go into action against North Korean forces at the village of Sojong-Ni, near Osan. At right is Private First Class Kenneth Shadrick, who was killed by enemy fire a few moments after this photo was made, thus becoming the first United States soldier to die in the Korean campaign.” Photo by Charles Turnbull. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

¶ 12Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

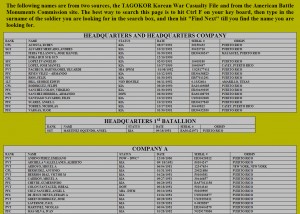

So appears Shadrick’s death in the archival record as represented in the Korean War Casualty File (TAGOKOR), 2/13/1950 – 12/31/1953, Records on Korean War Dead and Wounded Army Casualties, 1950 – 1970, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905 – 1981, Record Group 407, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.4 As described in the series scope and content note, the TAGOKOR file “contains information about U.S. Army officers and soldiers who were casualties in the Korean War.” The TAGOKOR file contains 109,975 records, detailing twenty different categories of casualties, including those killed, wounded, hospitalized, missing in action, and captured. Each record has twenty-six discrete units of coded information based on a variety of classification systems.

¶ 13Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Alongside the data itself, and available through the file’s technical documentation and accession dossier (the latter is the administrative documentation chronicling the file’s acquisition and administration by the National Archives and Records Administration [NARA]), is a wealth of information detailing TAGOKOR’s provenance, its circuitous custodial history, the actions taken to ensure its preservation, and the history of the many modes by which it has been made available to researchers and the public. This technical, managerial, and preservation documentation includes information as diverse as long-forgotten and poorly mimeographed military classification codebooks, key-punch instructions, physical transfer requests, preservation job summaries, access request correspondence, hash validation reports, and a maze of correspondence between military administrators, archivists, veterans, and private citizens. The documentation represents an accumulated body of information revealing the material and organizational ministrations and transformations through which this archival record has been acquired, preserved, and made available.

¶ 14Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

The story of TAGOKOR, then, is not just the story of the horrific events it sought to record, but also the story of its constitution and reconstitution by its custodians and users. From its origins as a statistical computing file, to its current accessibility both as a full ASCII data download and a searchable database through NARA’s Access to Archival Databases (AAD) portal,5 the history of TAGOKOR illuminates the complexity of managing, preserving, and making available digital archival records and the often circumstantial and regenerative methods through which archival materials are published. TAGOKOR also carries evidence of the evolving matrix of ephemeral classification systems and encoding methods applied to raw data to facilitate its use, transmission, and interpretability, as well as the subtle influences of the media types and protocols by which it has been migrated and reformatted.

¶ 15Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

TAGOKOR’s associated documentation and its online reconstruction document how digital historical records pass through frameworks of organizational management, hierarchies of description and control, shifting bureaucratic and regulatory environments, and variegated preservation processes in order to be made available for public use. To publish an archive is to undertake an action at once both forward looking and necessarily circumscribed. Promulgated anew in response to technological and epistemological change, yet bearing the vestiges of prior media, management, and classifications, digital archival records such as TAGOKOR offer a rich point of reflection upon the interplay of historical event, administrative custodianship, media preservation, public accessibility, and continuing reinterpretation.

¶ 18Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0Figure 2. “Cpl. Sam Ayala of Niles, Calif., Co. L, 7th RCT, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for medical evacuation from Hill 717, Cpl. Ayala was wounded while engaged in a bitter grenade battle with deeply entrenched Chinese Communism. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23541 (Brigham).” Image from U.S. Army.

¶ 19Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

Every record has its origin stories, both material and historical. TAGOKOR was the product of The Adjutant General’s Office (the “TAGO” of TAGOKOR), a unit created in 1907 that “maintained personnel records, developed data processing systems, and administered the nonunit reserve components of the U.S. Army.” Though abolished in 1986, with its duties assigned to a variety of successor agencies, The Adjutant General’s Office was responsible for maintaining personnel information on U.S. Army soldiers for a variety of conflicts, including the Korean War (the “KOR” of TAGOKOR).6 By the time of the Korean War, the Army was well versed in the use of machine data processing and the machine-readable physical record that facilitated automated tabulation, the punch card. Data processing using punched cards was first developed in the early 1800s by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who used punched cards in his “Jacquard Loom” to program textile-weaving patterns.7 Punch cards did not gain widespread public recognition until Herman Hollerith, an MIT professor who had patented a punch card machine, utilized his system for calculating the 1890 U.S. Census, dramatically shortening the time it took to compile the information and receiving widespread media attention in the process.8

¶ 20Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0Figure 3. August 30, 1890, cover of Scientific American depicting the Hollerith punch card machine (called the “Electrical Enumerating Mechanism”) processing the U.S. Census.

¶ 21Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

The history of computing is inseparable from the history of military technology, of course, with the first electronic general-use computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), developed at Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Ground to calculate artillery trajectories. (In the TAGOKOR dataset, “Branch of Service” for Artillery is coded AT in character position 33-34 and “Type of Casualty” for “Died as result of missile wound received in action” is coded DOW in character position 47-49 and 2 in “Detail Code” in character position 50.) The U.S. Army first used punch cards in World War I in enlistee testing, and punch cards were in wide use by the government and military throughout the 1920s and 1930s.9 Even the lexicon of punch card processing and military engagement became, at times, semantically entangled. Collier’s magazine, in 1940, referred to the punch card machine as a “statistical sausage grinder,” echoing a phrase commonly used to describe the carnage of many World War I battles.10 Use of punch cards by the army was widespread in World War II, handled by the Machine Record Units, Mobile (MRUs) in order to calculate many different types of troop information, including casualties. As is noted in a history of punch cards and the MRUs, “By preparing casualty punch cards, and transmitting them by air courier to The Adjutant General, MRUs made possible the notification of next of kin with unprecedented speed. These same casualty punch cards were used in compiling overall battle casualty reports, and in preparing a comprehensive round-up of World War II Honor Dead and Missing by state and county of residence.”11

¶ 23Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

The TAGOKOR file no doubt had a similar origin in the MRUs and ended up as a set of 109,975 punch cards recording casualty information for Army soldiers for the entirety of the Korean War (earliest casualty date in TAGOKOR is 1950-06-30 and the final date is 1953-07-28). By the mid-1960s, however, the Army was moving away from punch card machinery. A records survey by the AGO of its Data Preparation Branch, Data Processing Division, USADATCOM in 1964 “included a recommendation that action be taken to convert the punched card file of Korean War casualties to magnetic tape” in order “to dispose of a relatively inactive file of approximately 110,000 punched cards.”12 Curiously, prior to conversion the cards were sequenced by state, then by county within state, then alphabetically by individual name within county. This model was “dictated by past experience indicating that future research activity” would be based on requests by state and county. This first moment of preservation reformatting thus offers an early glimpse of how administrative decision-making, along with expectations of research use, shape the arrangement of, and access to, the historical record.

¶ 24Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0Figure 5. Memorandum from Colonel J. M. Gardner recommending conversion of the TAGOKOR punched card file to magnetic tape.

¶ 25Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

The card file was converted to seven-track magnetic tape, 556 BPI on November 3, 1964, and two copies were made. Once converted, the punch cards were destroyed, with one magnetic tape copy held by USADATCOM for five years (per its retention scheduling), and another shipped to the Army Records Center. Included with both tapes was a file folder of documents, labeled a “key” to the data, “to facilitate its use as a source of historical information.”13

¶ 27Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

With twenty-six different categories of information, the TAGOKOR data also contains over ten different methods of classification, many archaic, arcane, or lost to time. In addition to the “key” file, the data itself contains traces of its punch card origins and continued machine reproductions: transpositions, key-punch operator errors, and character translations from legacy encoding methods are scattered throughout the dataset. Each TAGOKOR record starts with an eighteen-character string of a casualty’s name. Though this field is mostly human readable, even this information has its own set of encoding protocols, as seen in correspondence between the Chief of the Records Reconstruction Branch of the National Personnel Records Center and officers of the Mortuary Affairs & Casualty Support Division of the U.S. Army, where the instructions for punching source-document data give directives such as “name to consist of alpha characters only,” “close up hyphenated names,” and “names with less than 18 characters will be left justified with remaining characters filled with spaces.”14

¶ 35Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0

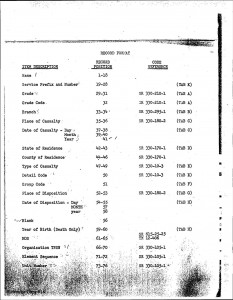

From there, the remaining sixty-seven character spaces in each record constitute a dizzying array of classification procedures, dependent upon a multiplicity of Department of The Army Special Regulations (SRs) and other code referents. “Place of Casualty” (character position 35-36) and “Place of Disposition” (character position 52-53) both require SR 330-180-2, “Foreign Station Code” of the “Statistical and Accounting Systems” classifications. Military Occupational Specialty (character position 61-65) requires SR 615-25-2, “Enlisted Personnel Classification Procedures,” and “Type of Casualty” and “Detail Code” (positions 47-49 and 50) require the “Battle Casualty Reporting” codebook SR 330-10-3.

¶ 36Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0Figure 8. Record Format in TAGOKOR “Key” documentation listing record item, character positions, and code references for the data.

¶ 37Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

“Without documentation for coded fields, individual data records often have little or no meaning,” writes Lee A. Gladwin, an electronic records archivist at NARA. His article, “Recovering and Breaking the U.S. Army and Air Force Order of Battle Codes, 1941-1945,” describes how codes for a World War II punch card set were “partly discovered or broken through the application of quantitative methods and recently discovered code documentation.”15 The riddle of cracking punch card codes has even been featured in journals of forensics analysis.16 As Gladwin notes, many coding systems can “be broken with a great deal of effort and a little luck,” though enigmas remain about the origins and use of many of these classification systems. As the first page of the TAGOKOR’s technical documentation succinctly states, “The documentation is necessary to understand the meaning of the digitized bits of information within the electronic records.”17 Electronic records like TAGOKOR thus exhibit dual dependencies, reliant not just on the interpretability of the machine-readable encodings of hardware and software (themselves often intertwined, interdependent) but also contingent on old mimeographed codebooks, obscure or difficult-to-locate print classification volumes, or often incomplete photocopies of legacy documentation. Servile to the pull of technological change, the whims of human signification, and the longevity of printed errata, early electronic data files and digital archival records like TAGOKOR exist at a distinct intersection of documentation, mechanism, and technological reconstitution that discommode ideas of trustworthiness, decipherability, and explication.

¶ 38Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0Figure 9. Sample page from the photocopied version of the SR 330-105-1 codebook made partially available in the TAGOKOR technical documentation.

¶ 39Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0

TAGOKOR, like the World War II datasets of Gladwin’s article, has its own decoding challenges. The file contains nine different SR classification systems and one Technical Manual classification (TM 12-406, Officer Classification Commissioned and Warrant: Classification and Coding of Civilian Occupations). Few of these are online or are easily accessible, but NARA archivists have located many of the codebooks, and portions have been scanned and included in the TAGOKOR technical documentation. Some encodings, however, are lost to time, as is detailed in a “Supplementary User Note” within the technical documentation: “The agency did not provide a meaning for the code ‘D’ in the Year of Disposition (YEAR_DISP) field.” Elsewhere in the technical documentation, four full pages are devoted to instructions for decoding unit information from the file. This can be done through near-cryptographic examination of the Troop Sequence Number, Element Sequence, and Unit Number fields (characters 66-76) using SR 330-105-1. “Some of the codes, especially those with ambiguous abbreviations in the attached documentation, may raise further research questions,” the guidance dryly notes.18

¶ 44Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0Figure 10. “Hit in the back during a grenade duel, Corporal Dominick F. Zegarelli, (Utica, N.Y.) Company L, 7th Regimental Combat Team, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for evacuation, while other members of his platoon rest. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23550 (Brigham).” Photo from U.S. Army.

¶ 45Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0

“At sixteen minutes and fifteen seconds past midnight on July 12, 1973, a typical warm and humid summer night in St. Louis, the first alarm reached the North Central County Fire Alarm System, Inc., the communications link for the many fire districts surrounding the center [National Personnel Records Center].”19

¶ 46Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0

“Fires, floods, and earthquakes have robbed us of many of the legacies of the past,” write Stender and Walker in their above-cited article on the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). But catastrophes can also have tangential, unforeseen influences on how archival materials come be appraised, acquired, or preserved. As NARA’s Center for Electronic Records (CER) sought to increase its acquisition of machine-readable records in the 1980s, the fact that the NPRC fire had destroyed an estimated 80 percent of U.S. Army personnel records from 1912 to 1960 influenced its decision to seek out and acquire other records and data files documenting this information.20 The intricacies of TAGOKOR’s custodial history match those of its classification systems, with the file having passed through successive departments and agencies prior to its acquisition by NARA. (Incidentally, the 1890 Census records, discussed previously as one of the first notable uses of punch cards and machine data processing by Hollerith, were themselves damaged in a fire at the U.S. Census building in 1921).21

¶ 47Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0

Once transferred to magnetic tape by the Army in 1964, the TAGOKOR file was distributed to both the AGO’s Data Processing Division and to the Department of the Army. The Army’s copy appears to have then ended up in the NPRC. In preliminary correspondence from NARA CER in 1989 inquiring about the availability of the original computer tape of TAGOKOR, the chief of NPRC’s Records Reconstruction Branch notes, “We were able to locate the original tape. It is a 7 track tape, 556 BPI, which was written on November 3, 1964 and received from the department of the Army on January 29, 1970. It was copied on to a 9 track tape, 1600 BPI, EBCDIC file that is standard DOS labeled.” The NPRC official then notes that though they could make a copy of the tape, they “do not have the programs to process the data,” their public-use version being a well-worn printout of the record fields along with the attendant key file.22

¶ 49Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0

Prior to NARA’s search for TAGOKOR, the file was delivered to other departments as well, including the Mortuary Affairs and Casualty Support Division of the Department of the Army, which requested a copy in the early 1980s. That request led the NPRC to note at the time that its own paper listing of TAGOKOR records “has suffered damage and is in need of replacement. Also the current format of the listings by state, county within state, and alphabetically based on the surname within the county, is no longer the most desirable format.”23 Changing expectations about research interest and evolving models of accessibility again had TAGOKOR’s custodians reconfiguring the outputs of the data for optimal usability.

¶ 50Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0

NARA has a rich legacy of acquiring and preserving electronic records, having accessioned its first electronic records—data related to the Tektite 1 program of aquanauts involved in sustained underwater marine research—on April 16, 1970.24 Between 1970 and TAGOKOR’s acquisition in 1989, however, NARA’s custodial program for managing electronic records fluctuated in response to administrative changes within the agency and according to larger governmental funding priorities. As Thomas Brown, former manager of CER has noted, “Since its establishment, the electronic records program has been directly effected by the larger presidential priorities.”25

¶ 51Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0

NARA as an agency has had a similarly uncertain bureaucratic history, having been created as an independent federal agency in 1934, then, in 1949, moved under the General Services Administration and renamed the National Archives and Records Service, only to be reestablished as an independent agency under its current name in 1985. Similar changes happened within the agency itself, with the departmental responsibility for electronic records being established as a branch, upgraded to a division, downgraded back to a branch, upgraded back to a division, and upgraded again to a center—all between 1968 and 1988.26 Staffing levels mirrored many of those changes and also occurred in the context of larger government-wide workforce reductions and expansions; electronic records staff over that time numbered from the single digits to well over fifty. The definitive history of NARA’s early work with electronic records, Thirty Years of Electronic Records, details the near-cyclical saga of the program blossoming, languishing, then rising again in its first three decades—developments often occurring in response to agency directives, presidential politics, and legal challenges involving presidential email and other electronic federal records (lawsuits for which NARA was often tasked with action even if not involved in the lawsuit itself). The pace of technological change had its impact as well, with NARA commissioning many preservation systems over the years, being forced to reassess prior appraisal guidelines due to hardware and software dependencies, making ongoing preservation format decisions as storage grew and new media types emerged, and steadily increasing the types of formats it accepted and the volume of born-digital materials it acquired.

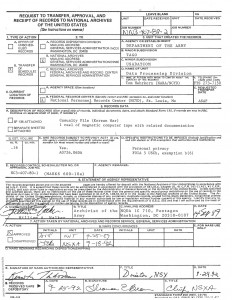

¶ 52Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0Figure 12. Request to Transfer, Approval, and Receipt of Records to the National Archives of the United States.

¶ 53Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

TAGOKOR was transferred to NARA in September 1989 from the Data Processing Division of the Adjutant General’s Office.27 The copy of TAGOKOR had been located at the NPRC, which itself had copied TAGOKOR from its first 7-track tape version, as described above. Thus, NARA received an open-reel, 9-track magnetic tape, in Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC). Given that TAGOKOR’s first preservation reformatting was in 1964, it makes sense that it used the EBCDIC encoding method, which was developed by IBM and used in its large mainframe computing systems of that era. The encoding system reveals its own punch card origins, with its non-continuous alphabet representation. This, along with its proprietary nature, was merely one of its many quirks that made EBCDIC the bane of programmers. The character encoding method is seldom, if ever, used today, long supplanted by more logical character encodings such as ASCII and Unicode. TAGOKOR’s binary encoding methods thus prove just as ephemeral and historically situated as the SR classification codes upon which its character abstractions are drawn. In the “Date of Casualty” field key in the technical documentation, for example, it specifies that the year 1950 can be deciphered by the “12 zone,” meaning the area of the punch card atop the 0-9 digit fields that comprise the card’s body. The “12 zone” could be punched to qualify the below fields. The EBCDIC-to-ASCII encoding has rendered this character as an ampersand. Indeed, occasional migration miscues and garbled translations appear as minor blemishes throughout the dataset and offer a reminder of the file’s passage through multiple methods of binary encoding.

¶ 55Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0

Other machine influences beyond bitstream patterns and character representation have exerted their influence on TAGOKOR during its time in the archive. Changes in technology also came to bear on the systems responsible for its ongoing custodianship and preservation. At the time TAGOKOR was formally transferred in September 1989, NARA itself lacked the equipment to access and read the file, having to rent time on mainframe systems at government computing centers. Earlier in the decade, NARA had reached an agreement with the National Institute of Health (NIH) to rent time on their IBM 360 mainframe system for accessing and copying records on 9-track open-reel tapes. TAGOKOR was first analyzed, for archival purposes, with the Data Interfile Transfer, Testing, and Operations Utility (DITTO), to determine the data labels and view some sample records. This preceded a more thorough analysis by the NIH computer center that was able to extract and copy the data labels and records, and provide some information on value frequencies and cross-tabulations. A backup copy was created, along with a duplicate “public use” copy. The file was also copied to an archival master 18-track, 27871 bpi, 3480 magnetic tape cartridge, which NARA had moved to as its preservation format two years prior.

¶ 56Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0

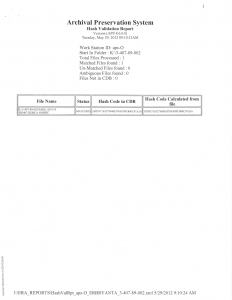

By 1991, the Archival Electronic Records Inspection and Control (AERIC) system had come online and allowed a more comprehensive verification of the records within the file. This more thorough analysis includes an examination of data elements, distinct values, null fields and records, and code frequency counts. Matched with known codebooks and the SRs required to interpret the data, AERIC offered a level of error identification and data analysis similar to what one would encounter using a spreadsheet or pivot table today. A few years later, in 1993, NARA launched the Archival Preservation System (APS). Driven by the exponential increase in electronic data files being transferred from agencies to NARA (NARA accessioned 150 electronic data files in 1988; four years later, in 1992, they accessioned 8,700), APS allowed greater custodial control of the electronic records once they were in the archive.28 It too was buffeted by outside legal and administrative events, as its prototype testing period instead became an immediate deployment not for custodial and preservation management but for basic media migration—all in response to ongoing lawsuits over the preservation of presidential email.

¶ 57Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

The TAGOKOR file was then preservation copied in 1999, in keeping with NARA’s policy of a ten-year cycle for media migration. This also allowed for a reappraisal of the redacted, public-use electronic copy of the file, including a recommendation that it be deaccessioned since it was deemed “superfluous” because of prior access decisions (described further in the next section). The file was then “formally verified” in the AERIC system. As the formal verification report states, “This file contains a number of inconsistencies between the documentation and the data and a number of fields containing no data. These inconsistencies reflect the use of the records for administrative purpose and not necessarily for statistical analysis. Therefore, researchers will discover numerous mis-codings (‘typos’) in a number of fields.”29

¶ 59Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

In 2012, the file was then migrated into NARA’s Electronic Records Archive (ERA) system. The history of ERA merits its own essay, but broadly stated, the system integrates and extends some of the functions of APS and AERIC while also building an integrated environment for transfer, accessioning, preservation, and online accessibility to the electronic records in the system. TAGOKOR’s migration into ERA was accompanied by hash validation reports and other technical and custodial reporting and authentication. The evolution of analysis and preservation systems has allowed both greater understanding of the dataset’s content (and its weaknesses and inaccuracies) and enabled new methods of access and delivery to users.

¶ 63Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0Figure 15. “Sfc. Louis F. Walz (left), a member of Co. E, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, and Pfc. Raymond M. Szukla, a member of Co. G, 5th Regimental Combat Team, 24th Infantry Division, receive medical aid at the 8063rd Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, attached to I Corps in Korea. Sfc. Walz is recovering from a head wound, and Pfc. Szukla suffered a wound in the right leg while engaged in action against the Communist-led North Korean forces. 4 November 1950. Korea. Signal Corps Photo #8A/FEC-50-21377 (McIntosh).” Photo U.S. Army.

¶ 64Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0

Digital preservation is often referred to as the process of ensuring access over time. Much as expectations of reference requests and use have influenced how TAGOKOR’s records were rearranged for public use, so have more contemporary legal contexts and communication systems driven how TAGOKOR is made available to researchers.

¶ 66Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0

TAGOKOR was first made accessible within the NPRC as a computer printout of the raw records and organized according to state and other location-based elements. As previously noted, early correspondence between NPRC and the U.S. Army’s Mortuary and Casualty Affairs department described the inadequacy of this arrangement, as well as the deterioration of the printed version due to “extensive use.” In seeking to create a copy of the machine-readable tape of TAGOKOR, the NPRC also included guidelines for a “desirable output,” originally requested for reproduction on microfiche (it was instead delivered as a copy of the 9-track open-reel magnetic tape).30

¶ 68Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0

Once accessioned by NARA, TAGOKOR was published in a variety of formats, including both print and digital versions. Researchers could use a number of print copies, some partially decoded, as well as supplementary research materials. “Because of the heavy reference use afforded TAGOKOR, the Center has generated numerous supplementary reference materials including printouts, reference reports, SPSS Control Cards, and frequencies generated from the statistical analysis,” notes a document in the accession dossier.31 The frequency lists were intended to give a numeric overview of the quantitative information in the data set, the occurrence of the codes used in specific fields, and so forth. In addition, NARA originally offered a tape copy of the TAGOKOR file on both 9-track reel and 3480-class tape cartridge, encoded in either ASCII or EBCIDIC format.

¶ 69Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0

However, the version of TAGOKOR that was being published in the early 1990s was not the entirety of the file. As a memo in the accession dossier notes, “Appropriate information in the records of nonfatal Army casualties has been masked in a public-use version of the data file. Each character of the name and service number have been replaced with a ‘#’ in all records not indicating death.”32 This action was premised on Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) statute b(6) that protects personal information, since many of the wounded veterans in the TAGOKOR file were still alive.

¶ 70Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0

“The denial of access to the Korean War Casualty File (TABOKOR) [sic], contained in a January 4, 1993, letter from Claudine J. Weiher, is reversed. The Center for Electronic Records will provide you with a copy … with all variables included.”33 This 1993 letter, from Raymond Mosley, Acting Deputy Archivist, was in response to the repeated appeals of denial of access to TAGOKOR by Joseph I. Hess of the 2nd Infantry Division Association. Hess had appealed his FOIA denial on the grounds that the Department of Defense had already released casualty information as press releases at the time of the conflict, and those records were themselves made available to researchers by the National Archives as paper archival copies in other collections. Changing legal contexts, FOIA interpretations, and appeals of reference request denials (not to mention the representation of some TAGOKOR data in other archival collections within NARA) all influenced how the archival records in TAGOKOR have been published.34 Lest Joseph Hess’s FOIA appeal seem peculiar, within TAGOKOR is Hess’s own casualty record:

¶ 72Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0

Research interest from Korean War veterans such as Joseph Hess drove availability of the full TAGOKOR file through FOIA requests, but the emergence of the World Wide Web created a means by which TAGOKOR’s records could be shared and republished for use outside of NARA. While NARA had long provided TAGOKOR in many formats, including electronic ones, TAGOKOR’s early appearance on the web reflects the characteristics of that medium—its quirks of design, methods of arrangement and access, and also its ephemerality. These websites provide their own parallel narrative of the retransmission and recontextualization of the TAGOKOR file.

¶ 73Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0

Due to family health conditions, this “Korean War Casualty” web site has been removed from the internet. We sincerely hope that during its five year existence it has been of some help to you, and hopefully we can bring it back to you at some future date. Please Remember Our Veterans……… Whitey Reese.35

¶ 75Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0

The above message, listed on the website of Whitey Reese in an October 10, 2004 capture of his website, available through the Internet Archive, marks the absence of the “Ramblings of Whitey Reese” website (original URL: http://www.theriver.com/Public/gcompany/), an early attempt to provide a list of TAGOKOR’s records via the web. As the “General Notes” page describes, a “copy of this file [TAGOKOR] (along with code conversion documentation) was purchased from the National Archives and Records Administration by us (this web site) during the 3rd quarter of year 2000.” It also notes the incompleteness of the TAGOKOR file as well as the many errors and miscodings within its data. With an admirable spirit towards authenticity, the website explains, “This policy [of not correcting errors in the data] is implemented due to the fact that these listings have been extracted from an historical document and should accurately portray the natural existence of the document whether it contains informational errors or not.”36 Viewing the many captures of the website over time, a contemporary user cannot help but feel a nostalgic charm, no doubt evoked by the animated gifs, the blinking “click here” buttons, and the lengthy list of html tables—all reminders of early web design, syntax, and construction. That TAGOKOR’s reuse can be so historically situated, dependent upon the customs and visual aesthetics of early networked technologies, is a reminder of the file’s ongoing, alternate existence outside the custody of the National Archive. One can only ponder the number of early internet researchers who accessed this copy of the file over the version available in NARA’s reading rooms.

¶ 77Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0

Of course the TAGOKOR file was used by other sites, such as the Borinqueneers Website, which commemorates the contributions of Puerto Rican troops to the Korean War, and the Korean War Project, a site that aggregates information from a variety of datasets to document the history of the conflict.37 Many of these sites combine TAGOKOR with related archival materials, such as those listing Marine or support personnel casualty information (TAGOKOR, as a reminder, only recorded U.S. Army casualties), or they mix and match TAGOKOR data with other files to highlight a specific unit, to verify service records and awards, or to substantiate years of service or dates of casualty. TAGOKOR has informed the casualty listings offline as well, providing troop listings for monuments and memorials, including those seeking to recognize veterans according to hometown or geographic area.

¶ 78Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0

The Whitey Reese website makes it clear that the decoding and decipherability of the TAGOKOR file, however, has been the work of the user in the past. Public-use versions of the file have been arranged in ways that best enabled ease of search, and full copies of the file have been made available; but, access to individual records within the dataset required users either to request a full copy on media and decode it themselves or visit NARA. That changed in 2003, with the launch of the Access to Archive Database system (AAD), which allows users to search, query, and download portions of born-digital archival data files. The AAD currently provides access to almost 500 electronic files and databases containing around 85 million individual records.

Figure 20. Kenneth Shadrick record as seen in the downloadable TAGOKOR ASCII file viewed in a text editor, on Whitey Reese’s website, on The Korean War Project website, and on NARA’s AAD system.

Figure 20. Kenneth Shadrick record as seen in the downloadable TAGOKOR ASCII file viewed in a text editor, on Whitey Reese’s website, on The Korean War Project website, and on NARA’s AAD system.

Figure 20. Kenneth Shadrick record as seen in the downloadable TAGOKOR ASCII file viewed in a text editor.

Figure 20. Kenneth Shadrick record as seen in the downloadable TAGOKOR ASCII file viewed in a text editor, on Whitey Reese’s website, on The Korean War Project website, and on NARA’s AAD system.

¶ 80Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0

The availability of the original data file allows for more contemporary reconstructions of TAGOKOR. These might employ a number of different new encoding and accessibility techniques. Contemporary data editing applications allow for user-driven deciphering, code frequency analysis, error identification and correction, and similar parsing and unraveling of the records. The availability of the full dataset also allows for the creation of data visualizations of the information and other novel methods by which to query and interpret the full extent of the 109,975 records in the file. While the database powering AAD allows for limited user querying, encoding the available TAGOKOR data into more semantic, machine-friendly formats would enable further expansion of the file’s accessibility and reuse, including making it machine-readable to web applications. This would allow the TAGOKOR file to be linked with other related datasets, collections, and primary source materials.

¶ 83Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0

After the shooting stopped the guards went around sticking everybody with bayonets, to make sure we were dead. They only got me in the kneecap. There was somebody on top of me, and I think the guards were in a hurry to leave by then.… But I never talked about any of this before. You can’t understand this kind of experience unless you’ve been through it.… Well, you can read about it all you want, but you’re not going to understand how it was.38

¶ 84Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0

Lloyd Kreider’s harrowing tale of capture and attempted execution reminds us that TAGOKOR is not only an electronic record, not just holes in a punch card, fluxes on magnetic tape, bits on a disk, or tables on a webpage. It is also a representation, incomplete yet significant, of many tragic stories of human experience—stories simultaneously lost to time, evoked by their incomplete representation in documents, photographs, or electronic records, and also continually regenerated according to the fluctuations of law, culture, and technology. The file’s context is expansive, limitless even, as it continues to be reinterpreted by users; but it is also woefully dependent, inextricably bound to the media, encodings, classifications, and descriptions through which it is preserved and made available. “The past is a foreign country whose features are shaped by today’s predilections,” David Lowenthal has written, “its strangeness domesticated by our own preservation of its vestiges.”39

¶ 85Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0

From EBCDIC to ASCII, from punch card to magnetic reel tape, and tape cartridge to spinning disk, as an electronic archival record, TAGOKOR has spanned a variety of media types and has been processed and reprocessed in a number of binary encodings. Each has left its trace upon how TAGOKOR, as a record, is inscribed, described, and preserved. Concomitant with this media evolution has been the variety of ways that TAGOKOR has been made accessible to, and interpreted by, researchers and the public, and how it has accrued the lineaments—technological and managerial—of its ongoing administration. TAGOKOR offers such a rich point of reflection on the nature of digital records because its origin as a statistical file seems to exist at such great conceptual distance not just from the tragedies, the literal mortalities, it tabulates, but because it exists as both calculation and abstraction. Its complicated administrative history, FOIA status, and preservation actions provide a distinct counterpoint to the brutal weight of the multitudinous human epochs it carries through time.

¶ 86Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0

TAGOKOR also offers an illuminating example of a number of the unforeseen ways that records can come to be collected for the archive, the sometimes ad-hoc nature of early digital preservation efforts, and how networked technology has allowed for a method of public reuse and recreation seeded by, yet exterior to, the custodial institution. In fact, TAGOKOR’s story contains what can be seen as a unique pivot point between preservation and representation. At that moment when technical capability, technological infrastructure, and established best practices—as far as bit-level preservation—were understood and effectively administered by archivists, access issues began to morph. The changing legal context due to FOIA legislation and new access technologies allowed average users to provide their own methods of access to records and contextualize and describe them in personal, distinctive ways. As TAGOKOR the electronic record became better stabilized and validated, its representation became more unanchored, more refracted and restructured by users outside the archive and away from the paper printouts, key files, static interfaces, and legacy representations.

¶ 87Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0

That act of publishing, of representation and dissemination, becomes the thread by which the biography of TAGOKOR is sewn, the loom upon which its legacy is woven. A photographer asks a soldier to coordinate his actions so it can be photographed for publication back home; a correspondent publishes reports on a dead soldier’s “unreal” expression; a clerk keys encoded information on a punched card; those punched cards are later published onto magnetic tape, to spinning disk, to reference room printout and data download. At the same time, the record is sifted, sorted, culled, and republished to the World Wide Web, then published again as visualizations, as relational database, with contemporaneous classifications and encodings. With each migration, the original record accrues the minor influences of media or interpretation, always a bit further withdrawn from its original referents as it is impressed upon by unforeseen uses and new methods of description and delivery. It accumulates, over time, its own parallel history of elision and elaboration—a history separate from the literal preservation of the bit sequence itself, but one that elucidates the regenerative nature of preserved records.

¶ 88Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0

Similarly, historical contingency has played its own role in this narrative. Just as a combat photographer sought to record an image, and a war correspondent a story, elision and elaboration colored these events as well. For in fact, though widely hailed as the first American casualty of the Korean War due to the reporting of Marguerite Higgins and others, Kenneth Shadrick was actually not the first casualty of the conflict. Indeed even the TAGOKOR file lists the first casualty date as June 30, 1950, in reference to the deaths of those aboard an American aircraft that was destroyed soon after landing. Shadrick was merely the first widely reported death, the first casualty to appear in the communication networks of the era—a reported fact that, in this case, is contested by the archival record itself.

¶ 89Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0

“Whether captured in the blink of a shutter or accumulated over months and years of bookkeeping, inscriptions attest to the moments of their own inscription in the past. In this sense, they instantiate the history that produced them, and thus help to direct any retrospective sense of what history in general is.”40 TAGOKOR no doubt bears those legacies of its origin, but its biography resists categorization as a permanent static object. Attenuated through time materially, authenticated through time technologically, and compounded through time by annotation, dissemination, and republication, this digital record exists instead in an ongoing process of transformation, what Heather MacNeil has called “a continuous state of becoming … resituated in different environments and by different authorities.”41 Some social moments or technological processes have provided windows of stability in certain areas—hash validation can detect any bit-level change, raw data downloads can provide unmediated access—and flux and transition will not delineate all aspects of TAGOKOR or any other record group. But digital archival collections remain influenced by characteristics of media as much as by legal contexts of availability, as buffeted by administrative technologies of control and preservation as by social and cultural protocols and assumptions about reuse and circulation. Once published and available, there exist multiple copies of TAGOKOR, a multiplicity of variants, some circulating in networks and social channels of dissemination, some migrated forward as preservation masters, some—such as the original punch cards—signified purely through their faint remnants in obsolete encodings or classifications. Each individual re-creation carries the traces of its former representation and bears the hallmarks of its current conventions of access. Each navigates the tension between the original event, that historical nexus of occurrence and inscription, and its contemporary explication and uses. And so the biography of TAGOKOR, like all archival records, is one both already written and never completed, both continually becoming and terminally changeless, forever poised between incident and encoding, articulation and preservation, record and reinterpretation, finality and vitality.

¶ 91Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0Thanks are given to the staff at NARA’s Center for Electronic Records who met to talk about TAGOKOR and CER’s history, and to the Manhattan Research Libraries Initiative (MaRLI) program that provides independent researchers special access to the collections of Columbia University, New York University, and New York Public libraries.

Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall, “The Cultural Biography of Objects,” World Archaeology 31, no. 2 (1999): 170. [↩]

Spoken by “A Lump of Coal” in Annie Carey, Autobiographies of a Lump of Coal, a Grain of Salt, a Drop of Water, a Bit of Old Iron, a Piece of Flint (New York: Cassell, Petter, and Galphin, 1870), 22-23. Available through Google Books at http://books.google.com/books?id=JIcDAAAAQAAJ. [↩]

Lars Heide, Punched-Card Systems and the Early Information Explosion, 1880–1945 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 21-37. [↩]

Donald Fisher Harrison, “Computers, Electronic Data, and the Vietnam War,” Archivaria 26 (Summer 1998): 19. [↩]

Steven Lubar, “’Do Not Fold, Spindle, or Mutilate’: A Cultural History of the Punch Card,” Journal of American Culture 14, no. 4 (Winter 1992): 44. [↩]

Charles M. Province, “IBM Punch Card Systems in the U.S. Army,” The Patton Society, accessed March 15, 2014, http://pattonhq.com/ibm.html. [↩]

J. M. Gardner, Commander, USADATCOM, January 22, 1965, Technical Documentation for the Korean War Casualty File (TAGOKOR), 1950-1953 (p. 12), Records on Korean War Dead and Wounded Army Casualties, 1950-1970, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905-1981, Record Group 407, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD, accessed March 15, 2014, http://media.nara.gov/electronic-records/rg-407/tagokor/111.1DP.pdf. [↩]

David Petree, Director, National Personnel Records Center, to Dick Tobias, General Services Administration, January 24, 1984, Box 1, Korean War Casualty File, Records on Korean War Dead and Wounded Army Casualties, 1950-1970, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905-1981, Record Group 407, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [↩]

Erin M. Misunaga, “Cracking the Code: A Decode Strategy for the International Business Machines Punch Cards of Korean War Soldiers,” Journal of Forensic Science 51, no. 3 (May 2006): 617-23. [↩]

Records loss estimates from “The 1973 Fire, National Personnel Records Center,” The National Archives, accessed March 15, 2014, http://www.archives.gov/st-louis/military-personnel/fire-1973.html. The influence of the St. Louis fire in TAGOKOR’s acquisition was recounted in interviews with Center of Electronic Records staff. [↩]

John Gerfen, Chief, Records Reconstruction Branch, NPRC to Margaret Adams, Archives Specialist, CER, NARA, July 25, 1989, Box 1, Korean War Casualty File, RG 407, NACP. [↩]

Petree to Tobias, Box 1, Korean War Casualty File, RG 407, NACP. [↩]

Thomas Brown, “History of NARA’s Custodial Program for Electronic Records: From the Data Archives Staff to the Center for Electronic Records, 1968-1988,” in Thirty Years of Electronic Records, ed. Bruce Ambacher (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2003), 1. For information on the history of punch cards within NARA, see Margaret O’Neill Adams, “Punch Card Records: Precursors of Electronic Records,” The American Archivist 58 (Spring 1995): 182-201. [↩]

Brown, “History of NARA’s Custodial Program,” 19. [↩]

Request to Transfer, Approval, and Receipt of Records to the National Archives of the United States, Accession Dossier, Records on Korean War Dead and Wounded Army Casualties, 1950-1970 (TAGOKOR), RG 407, NACP. File obtained via FOIA request and made available online within the accession dossier available at http://jeffersonbailey.com/tagokor_data/tagokor_accession_dossier.pdf. [↩]

Bruch Ambacher, “The Evolution of Processing Procedures for Electronic Records,” in Ambacher, Thirty Years of Electronic Records, 48-49. [↩]

Lloyd Kreider, “Into the Tunnel,” in No Bugles, No Drums: An Oral History of the Korean War, ed. Rudy Tomedi (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993), 59. [↩]

David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), xvii. [↩]

Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 20. [↩]

TAGOKOR: Biography of an Electronic Record

By Jefferson Bailey

April 2014

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Not only do objects change through their existence but they often have the capability of accumulating histories, so that the present significance of an object derives from the person or events to which it is connected.1

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 In the golden age of our existence, not only did we enjoy the light and heat around us, but we carefully stored away considerable portions. These we now freely render up to you again, thus giving you another proof that nothing is ever really lost—nothing is ever actually destroyed.2

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 1 – Osan, Republic of Korea, July 1950

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 The attack came from the north. Leading the advance was a column of North Korean tanks followed by two regiments of North Korean troops numbering nearly 5,000 soldiers. Opposing this force was a group of around 400 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 24th Infantry Division, 21st Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bradford Smith, a group nicknamed “Task Force Smith.” The group had arrived in Korea only five days earlier, on July 1, 1950. They were among the first U.S. troops to arrive in Korea, having left Japan, where they were stationed, in response to the United Nations Security Council’s decision to send military forces to contest North Korea’s recent invasion of its southern neighbor, the Republic of Korea, on June 25, 1950. Task Force Smith was positioned in the hills north of the town of Osan, with the purpose of halting or delaying the North Korean advance in order to buy time for more U.S. forces to arrive in Korea.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Task Force Smith, however, was outmanned, had little combat experience, and was poorly equipped to battle a larger force with mechanized armor. The column of North Korean tanks swept through the first line of infantry defenses unscathed and continued down the main highway, where they encountered a small reconnaissance team of the 34th Regiment sent from battalion headquarters. This reconnaissance team attempted to destroy the tanks using their bazookas. One of these soldiers was Private First Class Kenneth Shadrick, from West Virginia. Also accompanying the team was Sergeant Charles Turnbull, an army combat photographer. No doubt spurred by the historic moment of that first day of engagement with an unknown enemy in an emerging conflict, Turnbull wanted photographs of the reconnaissance team as they fired their weapons, and Shadrick agreed to fire next. After firing from his foxhole, Shadrick rose up to assess his shot and was struck and killed by fire from the tank’s machine gun. Marguerite Higgins, the pioneer female war correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune, had witnessed the engagement from afar and was also present when Shadrick’s body was brought back to battalion headquarters. As she later wrote in her memoir,

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The stories that Higgins and other correspondents filed identified Kenneth Shadrick as the first reported American killed in action of what would come to be known as the Korean War.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 SHADRICK KENNETH RA15273308PV2GINL50507&54109KIA 1L505 7&31047451702460003411 9 \

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Figure1. “A team mans a Bazooka at the Battle of Osan. Members of the 24th Infantry Division, first United States ground units to reach the front, go into action against North Korean forces at the village of Sojong-Ni, near Osan. At right is Private First Class Kenneth Shadrick, who was killed by enemy fire a few moments after this photo was made, thus becoming the first United States soldier to die in the Korean campaign.” Photo by Charles Turnbull. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Figure1. “A team mans a Bazooka at the Battle of Osan. Members of the 24th Infantry Division, first United States ground units to reach the front, go into action against North Korean forces at the village of Sojong-Ni, near Osan. At right is Private First Class Kenneth Shadrick, who was killed by enemy fire a few moments after this photo was made, thus becoming the first United States soldier to die in the Korean campaign.” Photo by Charles Turnbull. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 So appears Shadrick’s death in the archival record as represented in the Korean War Casualty File (TAGOKOR), 2/13/1950 – 12/31/1953, Records on Korean War Dead and Wounded Army Casualties, 1950 – 1970, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905 – 1981, Record Group 407, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.4 As described in the series scope and content note, the TAGOKOR file “contains information about U.S. Army officers and soldiers who were casualties in the Korean War.” The TAGOKOR file contains 109,975 records, detailing twenty different categories of casualties, including those killed, wounded, hospitalized, missing in action, and captured. Each record has twenty-six discrete units of coded information based on a variety of classification systems.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Alongside the data itself, and available through the file’s technical documentation and accession dossier (the latter is the administrative documentation chronicling the file’s acquisition and administration by the National Archives and Records Administration [NARA]), is a wealth of information detailing TAGOKOR’s provenance, its circuitous custodial history, the actions taken to ensure its preservation, and the history of the many modes by which it has been made available to researchers and the public. This technical, managerial, and preservation documentation includes information as diverse as long-forgotten and poorly mimeographed military classification codebooks, key-punch instructions, physical transfer requests, preservation job summaries, access request correspondence, hash validation reports, and a maze of correspondence between military administrators, archivists, veterans, and private citizens. The documentation represents an accumulated body of information revealing the material and organizational ministrations and transformations through which this archival record has been acquired, preserved, and made available.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The story of TAGOKOR, then, is not just the story of the horrific events it sought to record, but also the story of its constitution and reconstitution by its custodians and users. From its origins as a statistical computing file, to its current accessibility both as a full ASCII data download and a searchable database through NARA’s Access to Archival Databases (AAD) portal,5 the history of TAGOKOR illuminates the complexity of managing, preserving, and making available digital archival records and the often circumstantial and regenerative methods through which archival materials are published. TAGOKOR also carries evidence of the evolving matrix of ephemeral classification systems and encoding methods applied to raw data to facilitate its use, transmission, and interpretability, as well as the subtle influences of the media types and protocols by which it has been migrated and reformatted.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 TAGOKOR’s associated documentation and its online reconstruction document how digital historical records pass through frameworks of organizational management, hierarchies of description and control, shifting bureaucratic and regulatory environments, and variegated preservation processes in order to be made available for public use. To publish an archive is to undertake an action at once both forward looking and necessarily circumscribed. Promulgated anew in response to technological and epistemological change, yet bearing the vestiges of prior media, management, and classifications, digital archival records such as TAGOKOR offer a rich point of reflection upon the interplay of historical event, administrative custodianship, media preservation, public accessibility, and continuing reinterpretation.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 2 – AYALA SAMMY L US56051176CPL5INLN0607A91001RTD4FL703 8A 047450700360000717 \

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Figure 2. “Cpl. Sam Ayala of Niles, Calif., Co. L, 7th RCT, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for medical evacuation from Hill 717, Cpl. Ayala was wounded while engaged in a bitter grenade battle with deeply entrenched Chinese Communism. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23541 (Brigham).” Image from U.S. Army.

Figure 2. “Cpl. Sam Ayala of Niles, Calif., Co. L, 7th RCT, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for medical evacuation from Hill 717, Cpl. Ayala was wounded while engaged in a bitter grenade battle with deeply entrenched Chinese Communism. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23541 (Brigham).” Image from U.S. Army.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Every record has its origin stories, both material and historical. TAGOKOR was the product of The Adjutant General’s Office (the “TAGO” of TAGOKOR), a unit created in 1907 that “maintained personnel records, developed data processing systems, and administered the nonunit reserve components of the U.S. Army.” Though abolished in 1986, with its duties assigned to a variety of successor agencies, The Adjutant General’s Office was responsible for maintaining personnel information on U.S. Army soldiers for a variety of conflicts, including the Korean War (the “KOR” of TAGOKOR).6 By the time of the Korean War, the Army was well versed in the use of machine data processing and the machine-readable physical record that facilitated automated tabulation, the punch card. Data processing using punched cards was first developed in the early 1800s by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who used punched cards in his “Jacquard Loom” to program textile-weaving patterns.7 Punch cards did not gain widespread public recognition until Herman Hollerith, an MIT professor who had patented a punch card machine, utilized his system for calculating the 1890 U.S. Census, dramatically shortening the time it took to compile the information and receiving widespread media attention in the process.8

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0![August 30, 1890, cover of Scientific American depicting the Hollerith punch card machine (called the “Electrical Enumerating Mechanism”) processing the U.S. Census.]](http://www.archivejournal.net/journal_2017/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/tagokor_003-213x300.jpg) Figure 3. August 30, 1890, cover of Scientific American depicting the Hollerith punch card machine (called the “Electrical Enumerating Mechanism”) processing the U.S. Census.

Figure 3. August 30, 1890, cover of Scientific American depicting the Hollerith punch card machine (called the “Electrical Enumerating Mechanism”) processing the U.S. Census.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 The history of computing is inseparable from the history of military technology, of course, with the first electronic general-use computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), developed at Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Ground to calculate artillery trajectories. (In the TAGOKOR dataset, “Branch of Service” for Artillery is coded AT in character position 33-34 and “Type of Casualty” for “Died as result of missile wound received in action” is coded DOW in character position 47-49 and 2 in “Detail Code” in character position 50.) The U.S. Army first used punch cards in World War I in enlistee testing, and punch cards were in wide use by the government and military throughout the 1920s and 1930s.9 Even the lexicon of punch card processing and military engagement became, at times, semantically entangled. Collier’s magazine, in 1940, referred to the punch card machine as a “statistical sausage grinder,” echoing a phrase commonly used to describe the carnage of many World War I battles.10 Use of punch cards by the army was widespread in World War II, handled by the Machine Record Units, Mobile (MRUs) in order to calculate many different types of troop information, including casualties. As is noted in a history of punch cards and the MRUs, “By preparing casualty punch cards, and transmitting them by air courier to The Adjutant General, MRUs made possible the notification of next of kin with unprecedented speed. These same casualty punch cards were used in compiling overall battle casualty reports, and in preparing a comprehensive round-up of World War II Honor Dead and Missing by state and county of residence.”11

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Figure 4. An IBM punch card typical of the type used for TAGOKOR.

Figure 4. An IBM punch card typical of the type used for TAGOKOR.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 The TAGOKOR file no doubt had a similar origin in the MRUs and ended up as a set of 109,975 punch cards recording casualty information for Army soldiers for the entirety of the Korean War (earliest casualty date in TAGOKOR is 1950-06-30 and the final date is 1953-07-28). By the mid-1960s, however, the Army was moving away from punch card machinery. A records survey by the AGO of its Data Preparation Branch, Data Processing Division, USADATCOM in 1964 “included a recommendation that action be taken to convert the punched card file of Korean War casualties to magnetic tape” in order “to dispose of a relatively inactive file of approximately 110,000 punched cards.”12 Curiously, prior to conversion the cards were sequenced by state, then by county within state, then alphabetically by individual name within county. This model was “dictated by past experience indicating that future research activity” would be based on requests by state and county. This first moment of preservation reformatting thus offers an early glimpse of how administrative decision-making, along with expectations of research use, shape the arrangement of, and access to, the historical record.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Figure 5. Memorandum from Colonel J. M. Gardner recommending conversion of the TAGOKOR punched card file to magnetic tape.

Figure 5. Memorandum from Colonel J. M. Gardner recommending conversion of the TAGOKOR punched card file to magnetic tape.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The card file was converted to seven-track magnetic tape, 556 BPI on November 3, 1964, and two copies were made. Once converted, the punch cards were destroyed, with one magnetic tape copy held by USADATCOM for five years (per its retention scheduling), and another shipped to the Army Records Center. Included with both tapes was a file folder of documents, labeled a “key” to the data, “to facilitate its use as a source of historical information.”13

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Figure 6. Cover page of the “Key to KOREAN CASUALTY FILE.”

Figure 6. Cover page of the “Key to KOREAN CASUALTY FILE.”

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 With twenty-six different categories of information, the TAGOKOR data also contains over ten different methods of classification, many archaic, arcane, or lost to time. In addition to the “key” file, the data itself contains traces of its punch card origins and continued machine reproductions: transpositions, key-punch operator errors, and character translations from legacy encoding methods are scattered throughout the dataset. Each TAGOKOR record starts with an eighteen-character string of a casualty’s name. Though this field is mostly human readable, even this information has its own set of encoding protocols, as seen in correspondence between the Chief of the Records Reconstruction Branch of the National Personnel Records Center and officers of the Mortuary Affairs & Casualty Support Division of the U.S. Army, where the instructions for punching source-document data give directives such as “name to consist of alpha characters only,” “close up hyphenated names,” and “names with less than 18 characters will be left justified with remaining characters filled with spaces.”14

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 Figure 7a. “Key Punch Instructions.”

Figure 7a. “Key Punch Instructions.”

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 Figure 7b. “General Instruction for punching source document data.”

Figure 7b. “General Instruction for punching source document data.”

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 From there, the remaining sixty-seven character spaces in each record constitute a dizzying array of classification procedures, dependent upon a multiplicity of Department of The Army Special Regulations (SRs) and other code referents. “Place of Casualty” (character position 35-36) and “Place of Disposition” (character position 52-53) both require SR 330-180-2, “Foreign Station Code” of the “Statistical and Accounting Systems” classifications. Military Occupational Specialty (character position 61-65) requires SR 615-25-2, “Enlisted Personnel Classification Procedures,” and “Type of Casualty” and “Detail Code” (positions 47-49 and 50) require the “Battle Casualty Reporting” codebook SR 330-10-3.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 Figure 8. Record Format in TAGOKOR “Key” documentation listing record item, character positions, and code references for the data.

Figure 8. Record Format in TAGOKOR “Key” documentation listing record item, character positions, and code references for the data.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 “Without documentation for coded fields, individual data records often have little or no meaning,” writes Lee A. Gladwin, an electronic records archivist at NARA. His article, “Recovering and Breaking the U.S. Army and Air Force Order of Battle Codes, 1941-1945,” describes how codes for a World War II punch card set were “partly discovered or broken through the application of quantitative methods and recently discovered code documentation.”15 The riddle of cracking punch card codes has even been featured in journals of forensics analysis.16 As Gladwin notes, many coding systems can “be broken with a great deal of effort and a little luck,” though enigmas remain about the origins and use of many of these classification systems. As the first page of the TAGOKOR’s technical documentation succinctly states, “The documentation is necessary to understand the meaning of the digitized bits of information within the electronic records.”17 Electronic records like TAGOKOR thus exhibit dual dependencies, reliant not just on the interpretability of the machine-readable encodings of hardware and software (themselves often intertwined, interdependent) but also contingent on old mimeographed codebooks, obscure or difficult-to-locate print classification volumes, or often incomplete photocopies of legacy documentation. Servile to the pull of technological change, the whims of human signification, and the longevity of printed errata, early electronic data files and digital archival records like TAGOKOR exist at a distinct intersection of documentation, mechanism, and technological reconstitution that discommode ideas of trustworthiness, decipherability, and explication.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Figure 9. Sample page from the photocopied version of the SR 330-105-1 codebook made partially available in the TAGOKOR technical documentation.

Figure 9. Sample page from the photocopied version of the SR 330-105-1 codebook made partially available in the TAGOKOR technical documentation.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 TAGOKOR, like the World War II datasets of Gladwin’s article, has its own decoding challenges. The file contains nine different SR classification systems and one Technical Manual classification (TM 12-406, Officer Classification Commissioned and Warrant: Classification and Coding of Civilian Occupations). Few of these are online or are easily accessible, but NARA archivists have located many of the codebooks, and portions have been scanned and included in the TAGOKOR technical documentation. Some encodings, however, are lost to time, as is detailed in a “Supplementary User Note” within the technical documentation: “The agency did not provide a meaning for the code ‘D’ in the Year of Disposition (YEAR_DISP) field.” Elsewhere in the technical documentation, four full pages are devoted to instructions for decoding unit information from the file. This can be done through near-cryptographic examination of the Troop Sequence Number, Element Sequence, and Unit Number fields (characters 66-76) using SR 330-105-1. “Some of the codes, especially those with ambiguous abbreviations in the attached documentation, may raise further research questions,” the guidance dryly notes.18

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 3 – ZEGARELLI DOMINICKRA12112109CPL5INLN0307A23065RTD4F 29 7A 027040700360000711 \

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 Figure 10. “Hit in the back during a grenade duel, Corporal Dominick F. Zegarelli, (Utica, N.Y.) Company L, 7th Regimental Combat Team, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for evacuation, while other members of his platoon rest. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23550 (Brigham).” Photo from U.S. Army.

Figure 10. “Hit in the back during a grenade duel, Corporal Dominick F. Zegarelli, (Utica, N.Y.) Company L, 7th Regimental Combat Team, U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, waits for evacuation, while other members of his platoon rest. 3 July 1951. Korea. Photo from U.S. Army Signal Corps archive. Photo #8A/FEC-51-23550 (Brigham).” Photo from U.S. Army.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 “Fires, floods, and earthquakes have robbed us of many of the legacies of the past,” write Stender and Walker in their above-cited article on the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). But catastrophes can also have tangential, unforeseen influences on how archival materials come be appraised, acquired, or preserved. As NARA’s Center for Electronic Records (CER) sought to increase its acquisition of machine-readable records in the 1980s, the fact that the NPRC fire had destroyed an estimated 80 percent of U.S. Army personnel records from 1912 to 1960 influenced its decision to seek out and acquire other records and data files documenting this information.20 The intricacies of TAGOKOR’s custodial history match those of its classification systems, with the file having passed through successive departments and agencies prior to its acquisition by NARA. (Incidentally, the 1890 Census records, discussed previously as one of the first notable uses of punch cards and machine data processing by Hollerith, were themselves damaged in a fire at the U.S. Census building in 1921).21

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Once transferred to magnetic tape by the Army in 1964, the TAGOKOR file was distributed to both the AGO’s Data Processing Division and to the Department of the Army. The Army’s copy appears to have then ended up in the NPRC. In preliminary correspondence from NARA CER in 1989 inquiring about the availability of the original computer tape of TAGOKOR, the chief of NPRC’s Records Reconstruction Branch notes, “We were able to locate the original tape. It is a 7 track tape, 556 BPI, which was written on November 3, 1964 and received from the department of the Army on January 29, 1970. It was copied on to a 9 track tape, 1600 BPI, EBCDIC file that is standard DOS labeled.” The NPRC official then notes that though they could make a copy of the tape, they “do not have the programs to process the data,” their public-use version being a well-worn printout of the record fields along with the attendant key file.22

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Figure 11. NPRC request for new file.

Figure 11. NPRC request for new file.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Prior to NARA’s search for TAGOKOR, the file was delivered to other departments as well, including the Mortuary Affairs and Casualty Support Division of the Department of the Army, which requested a copy in the early 1980s. That request led the NPRC to note at the time that its own paper listing of TAGOKOR records “has suffered damage and is in need of replacement. Also the current format of the listings by state, county within state, and alphabetically based on the surname within the county, is no longer the most desirable format.”23 Changing expectations about research interest and evolving models of accessibility again had TAGOKOR’s custodians reconfiguring the outputs of the data for optimal usability.