Unrolling the Past: The Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions

By

Nicole Topich

April 2014

In January 2013, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Archives of the Commonwealth began work on identifying, cataloging, and digitizing thousands of anti-slavery petitions collected in the Archives. The goal of the project, which is funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, is to provide access to previously unseen documents written between 1783 and 1870 in what has effectively been a “hidden collection” and, once these materials have been digitized, to explore innovative methods and approaches for digital scholarship. Daniel Carpenter, the Allie S. Freed Professor of Government at Harvard and the principal investigator of the project, will be using the extensive data collected to analyze and compare petitioning across various time periods and geographies. We believe that the digitization and organization of the abundant, detailed information contained in individual petitions will also serve scholars.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

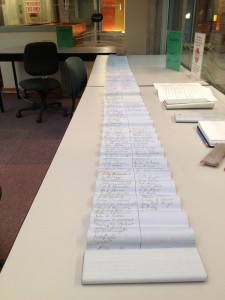

Figure 1. A petition from the anti-slavery project in the Massachusetts Archives reading room. Passed Acts. Acts of 1855, chapter 489, petition of R. E. Apthorp. SC1/series 229X. Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts. Photograph by author.

Figure 1. A petition from the anti-slavery project in the Massachusetts Archives reading room. Passed Acts. Acts of 1855, chapter 489, petition of R. E. Apthorp. SC1/series 229X. Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts. Photograph by author.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The archived papers to be digitized include documents from the unpassed legislative collections of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate through 1870, materials from the passed legislation through 1870, and all collections created before 1783 at the Massachusetts Archives of the Commonwealth.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The simple creation of the digital collection will be one of the greatest benefits of the project, as it would be almost impossible for one researcher to examine everything in the physical collections and gain a comprehensive identification of the materials. The digital archive will allow the documents to be compiled in ways that would not be possible at the physical archives, fostering new perspectives and scholarly endeavors. In addition to evaluating individual images of the petitions, researchers will be able to use metadata and associated tools for structured and extensive comparisons.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Through significant data collection, the project aims to provide multiple points of access and analysis. It will experiment with the dynamic possibilities of digital scholarship, including network and geospatial analysis of petitioning across time and space in Massachusetts. Additional information on the petitions, such as addresses of the signatories, can also allow for detailed analysis and insights on the processes of circulation and canvassing. We will also be exploring the use of further tools to expand the project, including crowdsourced transcription, linked data, and multiple projects for curriculum development, education, and outreach. The scholarship potential of this information is broad, with such possibilities as:

- ¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

- tracing a family’s activity in petitioning (for example, see the Massachusetts families on this petition, including the Alcotts);

- linking the petitions with other data, such as organization rosters, to see if the petitions originated from a specific group or event, such as an anti-slavery fair (for example, it would be fascinating to research the origin of this petition, which includes among its many prominent signatures Lucy Stone, Henry Box Brown, and William and Ellen Craft, grouped together under the section “others,” as opposed to “legal voters”);

- using individual names to trace decisions across subjects or time through petitioning activities;

- or locating previously unstudied links between individuals (for example, William Lloyd Garrison apprenticed with Gamaliel W. Oliver, a shoemaker in Lynn, Massachusetts, in the year 1814 when he was nine years old; Oliver would lead several anti-slavery petitions (see two here and here) in the late 1830s).

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 As is often the case with grant projects involving archives, we encountered unexpected challenges. At the beginning of the project, we realized that the individual petitions described in the Massachusetts House of Representative’s Journal were not always included in the index of petitions. This nineteenth-century index is the only access point to the petitions in the Massachusetts unpassed legislation collections, which contain the majority of petitions for this project. The index includes the first signer’s last name, which theoretically can be linked to the subject of the petition by reading the Massachusetts House of Representatives or Senate journals; but the petition index proved to be incomplete. This led us to the decision that the archivist would examine every piece of House and Senate unpassed legislation from 1783 to 1870, a collection of hundreds of trays containing thousands of documents. With the indispensable support and assistance of the state archives, we have effected the comprehensive identification of documents for the project, including hundreds that had been previously unseen. Our new understanding of the scope of the legislative collections has led to several new ideas for extensions of the database and website; our next grant applications will aim to expand our mission by including petitions relating to women’s rights through 1925. This is a natural extension of the project because of the large quantities of petitions relating to women’s rights and the links between anti-slavery activism and early women’s suffrage activities. Although the project website has not been developed, images of the petitions are currently deposited and viewable through the Harvard University Library website. An example of the ties between anti-slavery efforts and women’s suffrage can be seen in this suffrage petition led by William Lloyd Garrison, which has the unusual placement of the women’s signatures on the left-hand side.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Although the digital archive is not held to the editorial standards of traditional publications, we conducted intensive research, sometimes at the petition or individual-signature level. In order to locate related petitions, we required a broad knowledge base, ranging from the anti-slavery movement and antebellum Massachusetts to the legal bureaucracy and record-keeping of the Massachusetts government. The project work will also include popular and academic publications for outreach and to legitimize our scholarship efforts, even beyond the traditionally defined fields of study in the social sciences and humanities.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

A bundle of anti-slavery petitions at the Massachusetts Archives before processing. Photograph by author.

A bundle of anti-slavery petitions at the Massachusetts Archives before processing. Photograph by author.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 We also felt it necessary to break from traditional library and information-science training in deciding to describe our materials at the item level. This was the only way to ensure proper scholarly analysis of such a vast collection of legal documents. We are gathering detailed data from each petition, including citation; location and date of the petition; legislative actions and dates; subject of the petition’s text; self-description of petitioners (including changes in their description, such as on this petition); total number of petitioners, with numbers broken down into gender and self-identified groups; three of the signatories; and whether the petition has self-identified groups separated, is printed, or includes minors. This is markedly different from the access that archives typically provide, and was made possible by devoting a staff member full-time to the partnership. The data is inherently subjective, just as previous descriptions and indexes of these materials were, but it will allow others to use and examine the new data or locate the individual documents and create their own data, descriptions, and analysis of the materials.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Project workflow presented a good number of challenges. By necessity, all processes were simultaneous, which can be difficult for a single staff member to handle. The core of the project is identifying, processing, cataloging, and arranging the digitization of the petitions, but there is pressure for such additional tasks as outreach, website and database development, grant applications, and planning. (The only factor that is certain about the future of digital archives is that they will change, as will the skills necessary for managing them.) Because I did not have a background in the project’s time period, geography, subject, or field, I had to educate myself. The background and perspective of an archivist is vital to a project like this one, but archivists in this position need to demonstrate not only training in various programs and tools, but also a willingness to learn more as new methods emerge and continually transform the field. By dedicating myself to this project from the beginning, I was able to gain the subject knowledge necessary for the later identification of relevant petitions from the archives and outreach to potential user groups. This newly acquired knowledge proved critical to the success and comprehensiveness of the project, including the more difficult identification of documents such as this one from Benjamin Franklin Sanborn describing his arrest for conspiring with John Brown.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 It has been difficult to decide which from among a plethora of tools and methods for digital archives will meet the future needs of the project—particularly for the expansion and preservation of the digital archives. In addition, we have focused on the scholarship of the project over the tools; if a tool does not fit the needs of our studies, we look for alternatives. We hope that this perspective will contribute to progress in building methodologies for digital scholarship, particularly for other scholars gathering large sets of documents and collecting data from underutilized archives.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 The project hopes to reach out to many different constituencies, including genealogists, academics, students, and the general public. Although these are not distinct groups, imagining how to connect with as many users as possible and raise awareness of the project with limited time and resources has been challenging. Adding to the outreach challenge, we also hope to further expand the project to include petitions from other geographic regions, time periods, and subjects, including petitions for women’s rights, Native American petitions, and federal petitions. Making all these documents digitally accessible makes many different research projects possible, contributing (we hope) to the general advancement of digital scholarship.1 Government and legal archives tend to draw less academic interest than other types of repositories do, possibly because of their organizational structures, but the document traces of the citizen’s interaction with the government have provided a treasure trove of petitions for our project. As Randall C. Jimerson points out, “Records in institutional archives are important as evidence, but they are also important as societal documentation.”2

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 This project is reimagining the possibilities for description of government and legislative collections that contain remarkable histories and individual stories. When I was an undergraduate working in archives, my perspective on the stories contained in them was significantly influenced after watching this video on Fred Wilson’s project at the Maryland Historical Society. For the digital archives project, I have seen how description, structure, and methods of finding aids can make a huge difference in access to archives, even in comparison to the approaches utilized by archivists and historians several decades ago. As Jennifer A. Gonzalez discusses in relation to Fred Wilson’s project, “The installations demonstrate how a given ‘order of things’ reveals its bias when consciously re-ordered, when traditionally mute objects are given the opportunity to ‘speak.’”3 One of the fundamental problems I am facing in my career as an archivist is how to deal with the overwhelming amount of unprocessed collections, and the changing access needs of users faced with inadequate descriptions from previous decades. We hope that the project will demonstrate how digital archives can be utilized to draw upon several archives and expose hidden collections. Rather than digitizing materials that have already been thoroughly described and studied, archives can utilize the exciting possibilities of digital projects to work with unprocessed or underutilized collections, which continue to be a major challenge for archives.4 It is my hope that archives will establish more mutually beneficial partnerships with researchers; there is a great interest in exploring digital scholarship possibilities, and projects could digitally assemble documents from several archives or utilize new methodologies and tools to provide new perspectives on existing collections. It will be key for creators of these projects to be open about their processes so that users can understand the context of a given project, including the limits in possibilities, subjects, or sources. As I realized the full scope of this project and its possibilities, I was reminded of Verne Harris’s discussion of the “four primary propositions (and energies) in their [Terry Cook’s and Helen Samuels’s] work”:

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 The archivist is not, in the first instance, a reader of and a worker with texts. Rather, she illuminates texts through an intense, critical, and multidisciplinary engagement with contexts. She is a purveyor of context, and of necessity pays the sharpest and broadest attention possible to it. The archivist must go beyond merely marking, or bemoaning, the many gaps in the documentary record. She is obliged to seek ways of filling those gaps, of bringing in those voices, those experiences, those memories—in short, those strangers—marginalised in or excluded from the record.5

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Acknowledgements:

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 The project would like to acknowledge the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities (PW-5105612) for funding for the cataloging and digitization of the petitions we are studying. We thank Martha Clark and Michael Comeau and the staff of the Massachusetts State Archives for efficient and generous assistance in locating, facilitating access and transferring petitions for digitization. Additional thanks to Maggie Hale and the Harvard College Library for their digitization work, to Lilia Halpern-Smith and Laura Donaldson of the Center for American Political Studies for administrative support on the project, and to the Academic Ventures at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. My deepest appreciation and thanks goes to Daniel Carpenter, the Allie S. Freed Professor of Government at Harvard University, whose tireless efforts and dedication have made the project possible. I remain responsible for all interpretations and errors.

- ¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

- For a recent discussion of this topic, see Edward L. Ayers, “Does Digital Scholarship Have a Future?” EDUCAUSE Review 48, no. 4 (July/August 2013), http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/does-digital-scholarship-have-future. [↩]

- Randall C. Jimerson, “How Archivists ‘Control the Past,’” in Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions, ed. Terry Cook (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2011), 373. [↩]

- Jennifer A. Gonzalez, “Fred Wilson: Material Museology,” in Fred Wilson: A Critical Reader, ed. Doro Globus (London: Ridinghouse, 2011), 356. [↩]

- J. M. Panitch, Special Collections in ARL Libraries: Results of the 1998 Survey Sponsored by the ARL Research Collections Committee (Washington, D.C.: Association of Research Libraries, 2001), http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/special-collections-arl-libraries.pdf. [↩]

- Verne Harris, “Ethics and the Archive: ‘An Incessant Movement of Recontextualisation,’” in Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions, ed. Terry Cook (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2011), 345-46. [↩]

Nicole Topich

Project Archivist, Center for American Political Studies – Harvard University

Impressive undertaking! As a historian (and descendant of Mass. abolitionists) I applaud and await!

Thanks so much for the work you do. Your project helps me puzzle out the history of my home town in Franklin Massachusetts and the lives of the African Americans who were enslaved there.

This digital collection is now available publicly at the following URL: http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/antislaverypetitionsma

Thank you for this awesome project! I’m currently researching Rev. Thomas F. Norris (1793-1853), editor of The Boston Olive Branch newspaper. He was actively involved with the anti-slavery movement. Well-known during his time, he did not leave a collection of personal papers. Your project looks like it will be an enormous help in piecing together this part of his many-faceted life apart from his newspaper.

I haven’t found anything on here yet, but I know that my second Great Grandfather, Henry Bozyol Hill of East Boston changed parties, because of the slavery issue and was a member of both the Ma. senate and the house of representatives.