The Archive of the Private Collection: Teaching an Undergraduate Seminar on Collecting

By

Virginia Anderson

September 2018

¶ 1Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

What does it mean to collect? Who collects, and why? How are collections formed and presented? Can you collect intangibles such as experiences or ideas? How does collecting enhance a collector’s quality of life, or help them to articulate a sense of identity? What are the responsibilities of institutions that come to house (formerly) private collections? In the fall of 2016, I taught a seminar, “Collecting and Cataloguing the Contemporary,” in the Program in Museums and Society at Johns Hopkins University that asked these questions. Undergraduates from Hopkins and from the Maryland Institute College of Art participated in the class, which combined a critical studies examination of private collecting with a practicum project, in which the students produced a catalogue of works in a local private collection.1 Students in the class were given access to an unusual archive: Baltimore-area collector Constance Caplan had invited us to study her extensive collection of modern and contemporary art, which includes examples of minimalist sculpture, Arte Povera, pop art, global postwar paintings and drawings, and photography. The intensive study of a “living” private collection magnified the students’ understandings of the circulation, display, and art-historical framework of contemporary art. And it advanced, in a very special way, the goal of this seminar: not to determine a single definition of collecting but to provide students with various critical frameworks for analyzing the gathering, retention, presentation, and function of items in a private collection of any kind.

¶ 2Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Teaching this class was an experiment in combining classroom instruction with applied archival research in a private collection, an uncommon setting for an academic experience. The readings and seminar discussions, stimulating in and of themselves, were applied to a particular case study, enriching the students’ engagement with the collector and the objects in her collection. In turn, the students’ experiences with the collector and those objects gave them personal and critical insight into their readings and discussions. Our syllabus included readings with sociological, psychological, economic, and historical perspectives on the practice of collecting. The early weeks of the class focused on how collecting has been defined by various authors and scholars in the field. We began with reading Walter Benjamin’s 1931 essay, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting” and continued on with studies by Susan M. Pearce, Russell Belk, Jean Baudrillard, and Stanley Cavell, among others. 2 Beginning with Benjamin’s statement that “Ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects,” the students found a range of definitions of collecting, from G. Thomas Tanselle arguing that collecting is limited to “the accumulation of tangible things” to Pearce’s assertion that “a collection exists if its owner thinks it does.”3 Through our readings, we developed a vocabulary around the act of collecting, whether seashells, bottle caps, or fine art. We considered the differences between accumulation and collecting, whether objects in a collection might retain their use-value or whether they are rendered sacred and removed from the circulation of everyday life, and how collections can be assessed along spectrums of authenticity and quality. They recognized themselves (and friends and relatives) as collectors and gained insights into the psychological dynamics of possession, mastery, and control that are brought into play through collecting.

¶ 3Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

The varied readings assigned to the students did not necessarily focus on art collecting per se, but rather offered a necessary bigger-picture perspective. Given the relatively elevated material costs of art collecting (compared to seashells, books, or stamps, among frequently collected objects), studies of art collecting have often focused on discussions of establishing value, the role of the marketplace, or the histories of canonical art dealers and collectors (see writings by Olav Velthuis or Malcolm Goldstein, for example, which we also read in the seminar). While these studies are quite useful, in this instance the goal was to allow the students to consider the role of the individual collector (the “private” in “private collector”?) from a nuanced and intimate perspective.

¶ 4Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Connie Caplan’s home and art collection served as our laboratory in two ways. For one, Ms. Caplan herself became the primary case study as we related the seminar readings to the real-life example of a collector, with the result that numerous discussions on this topic took place between her and the students. For example, they learned how she began collecting, what some of her motivations were, how she researched the works of art, how she acquired objects and worked with dealers and curators in a social network, and how she thought about the display of her collection in her home. This information was contextualized by the students within the broader body of knowledge they had gathered on the practices and outcomes of collecting, a process that invited a mutually empathetic perspective on the process of collecting, regardless of material cost or significance of cultural capital.

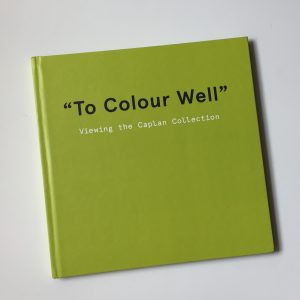

¶ 5Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0Figure 1. Book published by “Collecting and Cataloguing the Contemporary” class at Hopkins (with title quote by John Ruskin), designed by Janie Sanchez, one of the student authors. Photo: Virginia Anderson. Used with permission of designer.

¶ 6Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Secondly, Caplan’s collection spurred the main writing assignment for the seminar: as a final research project, each student authored an essay discussing a selection of eight to ten objects from the collection. After the end of the semester, these essays were compiled into a collection catalogue that we self-published. For the student authors, the discovery and study of “their” objects took place over the course of several field trips to the Caplan collection. To produce a catalogue essay with some authority, the students had to establish a sense of ownership and develop scholarly familiarity with their topic—a fairly big ask of undergraduate students who were not necessarily art history majors, much less specialists in modern and contemporary art. (I use the terminology of possession deliberately here, opening up possibilities for investigating the dynamic of ownership in which knowledge and experience, rather than currency, are exchanged for an authoritative relationship with a desirable object, as in the case of scholarly study). To facilitate this process, writing assignments helped to build a relationship between author and artwork, so the students progressed through personal responses to formal analyses and then to researched essays.

¶ 7Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

From the first writing assignment, a personal response essay, it was clear that studying the artworks in situ in a home environment strongly shaped how the students interacted with and observed the works of art. Many of the students’ observations focused on the placement of the art in the house in terms of how artworks interacted with each other, with the architecture of the house, and with the domestic surrounds of the dining table, the bed and nightstands, the desk. At this point, the intimacy of viewing art in the context of a home, bolstered by the texts we had read, opened their eyes to issues of possession, economic class, and conservation. In turn, these observations supported the formal dialogues they could see taking place between the art objects. The second writing assignment, a formal analysis of their assigned objects, also reflected how closely and carefully they were able to look, resulting in mentions of a loose thread emerging from a John Chamberlain sculpture, a brush hair embedded in the surface of a painted vase by Yayoi Kusama, the changing light and shadows around a Fred Sandback yarn installation in a stairwell. Most of these analyses, in the end, yielded observations or points of investigation that played a formative role in the direction each student took with their final paper.

¶ 8Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

The dynamics between private collections and museum collections were themselves a subject for our analysis. A visit to the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) provided an opportunity to learn more about a prominent private art collection donated to the museum, the Cone Collection of modern art, which was assembled during the first half of the twentieth century by the Baltimore-based sisters Claribel and Etta Cone. This collection offered a historical precedent within which to contextualize Ms. Caplan’s collection. We investigated the fate of private collections when they become part of an institution, either as part of a larger public collection as at the BMA, or when institutionalized as a whole, inviting comparison with additional case studies such as the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Our work with the Caplan collection enabled the students to understand how the meanings of a collection might shift as it moves from a state of ongoing flux in which its (living) owner acquires or deaccessions objects during his or her lifetime (or other periods of active collecting) to being fixed and memorialized in its entirety (and perhaps contextualized within a larger set of objects) in an institutional setting. By comparing our visits to the Caplan collection with our institutional field trip, the students could perceive more clearly how an object moves from being a marker of individual identity, and a reference point for personal memory, to a cultural sign that contributes to the establishment of an institutional identity.

¶ 9Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Working with the archive offered by this substantive private collection (and, it must be noted, under the auspices of a collector who very openly shared her experiences and her objects with us) gave the students in this class hands-on experience engaging with art objects and with producing original writing about that art. As a professor, I can see the impact that the empirical study of a collection had on my students’ critical understanding of the practice of collecting. It gave them personalized and empathetic insight into the psychology, social function, art-historical role, and institutional impact of private collecting, allowing them to come to possess a deeper understanding of possession itself.

The Program in Museums and Society frequently offers classes with a practicum aspect: students have helped to organize exhibitions at area museums and produced explanatory texts for murals or buildings on the Hopkins campus, for example. See the September 2016 Archive Journal essay by Rena Hoisington, Senior Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art, on her class and subsequent exhibition of artists’ books at http://www.archivejournal.net/notes/some-thoughts-on-working-with-students-to-organize-an-exhibition-of-artists-books/. [↩]

See Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1969), 59–67; Susan M. Pearce, Collecting in Contemporary Practice (London: SAGE Publications, 1998); and Russell W. Belk, “Collectors and Collecting,” in Interpreting Objects and Collections, ed. Susan M. Pearce (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 317–26; Jean Baudrillard “The System of Collecting,” (1968) in The Cultures of Collecting, eds. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994), 7–24; Stanley Cavell, “The World of Things: Collecting Thoughts on Collecting,” in Contemporary Collecting: Objects, Practices, and the Fate of Things, eds. Kevin Moist and David Banash (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013), 99–130. [↩]

Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” 67; G. Thomas Tanselle, “A Rationale of Collecting,” Studies in Bibliography 51 (1998): 1; Susan M. Pearce, Collecting in Contemporary Practice, 3. [↩]

Virginia Anderson

Adjunct Professor, Program in

Museums & Society – Johns Hopkins University

The Archive of the Private Collection: Teaching an Undergraduate Seminar on Collecting

By Virginia Anderson

September 2018

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 What does it mean to collect? Who collects, and why? How are collections formed and presented? Can you collect intangibles such as experiences or ideas? How does collecting enhance a collector’s quality of life, or help them to articulate a sense of identity? What are the responsibilities of institutions that come to house (formerly) private collections? In the fall of 2016, I taught a seminar, “Collecting and Cataloguing the Contemporary,” in the Program in Museums and Society at Johns Hopkins University that asked these questions. Undergraduates from Hopkins and from the Maryland Institute College of Art participated in the class, which combined a critical studies examination of private collecting with a practicum project, in which the students produced a catalogue of works in a local private collection.1 Students in the class were given access to an unusual archive: Baltimore-area collector Constance Caplan had invited us to study her extensive collection of modern and contemporary art, which includes examples of minimalist sculpture, Arte Povera, pop art, global postwar paintings and drawings, and photography. The intensive study of a “living” private collection magnified the students’ understandings of the circulation, display, and art-historical framework of contemporary art. And it advanced, in a very special way, the goal of this seminar: not to determine a single definition of collecting but to provide students with various critical frameworks for analyzing the gathering, retention, presentation, and function of items in a private collection of any kind.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Teaching this class was an experiment in combining classroom instruction with applied archival research in a private collection, an uncommon setting for an academic experience. The readings and seminar discussions, stimulating in and of themselves, were applied to a particular case study, enriching the students’ engagement with the collector and the objects in her collection. In turn, the students’ experiences with the collector and those objects gave them personal and critical insight into their readings and discussions. Our syllabus included readings with sociological, psychological, economic, and historical perspectives on the practice of collecting. The early weeks of the class focused on how collecting has been defined by various authors and scholars in the field. We began with reading Walter Benjamin’s 1931 essay, “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting” and continued on with studies by Susan M. Pearce, Russell Belk, Jean Baudrillard, and Stanley Cavell, among others. 2 Beginning with Benjamin’s statement that “Ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects,” the students found a range of definitions of collecting, from G. Thomas Tanselle arguing that collecting is limited to “the accumulation of tangible things” to Pearce’s assertion that “a collection exists if its owner thinks it does.”3 Through our readings, we developed a vocabulary around the act of collecting, whether seashells, bottle caps, or fine art. We considered the differences between accumulation and collecting, whether objects in a collection might retain their use-value or whether they are rendered sacred and removed from the circulation of everyday life, and how collections can be assessed along spectrums of authenticity and quality. They recognized themselves (and friends and relatives) as collectors and gained insights into the psychological dynamics of possession, mastery, and control that are brought into play through collecting.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The varied readings assigned to the students did not necessarily focus on art collecting per se, but rather offered a necessary bigger-picture perspective. Given the relatively elevated material costs of art collecting (compared to seashells, books, or stamps, among frequently collected objects), studies of art collecting have often focused on discussions of establishing value, the role of the marketplace, or the histories of canonical art dealers and collectors (see writings by Olav Velthuis or Malcolm Goldstein, for example, which we also read in the seminar). While these studies are quite useful, in this instance the goal was to allow the students to consider the role of the individual collector (the “private” in “private collector”?) from a nuanced and intimate perspective.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Connie Caplan’s home and art collection served as our laboratory in two ways. For one, Ms. Caplan herself became the primary case study as we related the seminar readings to the real-life example of a collector, with the result that numerous discussions on this topic took place between her and the students. For example, they learned how she began collecting, what some of her motivations were, how she researched the works of art, how she acquired objects and worked with dealers and curators in a social network, and how she thought about the display of her collection in her home. This information was contextualized by the students within the broader body of knowledge they had gathered on the practices and outcomes of collecting, a process that invited a mutually empathetic perspective on the process of collecting, regardless of material cost or significance of cultural capital.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Figure 1. Book published by “Collecting and Cataloguing the Contemporary” class at Hopkins (with title quote by John Ruskin), designed by Janie Sanchez, one of the student authors. Photo: Virginia Anderson. Used with permission of designer.

Figure 1. Book published by “Collecting and Cataloguing the Contemporary” class at Hopkins (with title quote by John Ruskin), designed by Janie Sanchez, one of the student authors. Photo: Virginia Anderson. Used with permission of designer.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Secondly, Caplan’s collection spurred the main writing assignment for the seminar: as a final research project, each student authored an essay discussing a selection of eight to ten objects from the collection. After the end of the semester, these essays were compiled into a collection catalogue that we self-published. For the student authors, the discovery and study of “their” objects took place over the course of several field trips to the Caplan collection. To produce a catalogue essay with some authority, the students had to establish a sense of ownership and develop scholarly familiarity with their topic—a fairly big ask of undergraduate students who were not necessarily art history majors, much less specialists in modern and contemporary art. (I use the terminology of possession deliberately here, opening up possibilities for investigating the dynamic of ownership in which knowledge and experience, rather than currency, are exchanged for an authoritative relationship with a desirable object, as in the case of scholarly study). To facilitate this process, writing assignments helped to build a relationship between author and artwork, so the students progressed through personal responses to formal analyses and then to researched essays.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 From the first writing assignment, a personal response essay, it was clear that studying the artworks in situ in a home environment strongly shaped how the students interacted with and observed the works of art. Many of the students’ observations focused on the placement of the art in the house in terms of how artworks interacted with each other, with the architecture of the house, and with the domestic surrounds of the dining table, the bed and nightstands, the desk. At this point, the intimacy of viewing art in the context of a home, bolstered by the texts we had read, opened their eyes to issues of possession, economic class, and conservation. In turn, these observations supported the formal dialogues they could see taking place between the art objects. The second writing assignment, a formal analysis of their assigned objects, also reflected how closely and carefully they were able to look, resulting in mentions of a loose thread emerging from a John Chamberlain sculpture, a brush hair embedded in the surface of a painted vase by Yayoi Kusama, the changing light and shadows around a Fred Sandback yarn installation in a stairwell. Most of these analyses, in the end, yielded observations or points of investigation that played a formative role in the direction each student took with their final paper.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The dynamics between private collections and museum collections were themselves a subject for our analysis. A visit to the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) provided an opportunity to learn more about a prominent private art collection donated to the museum, the Cone Collection of modern art, which was assembled during the first half of the twentieth century by the Baltimore-based sisters Claribel and Etta Cone. This collection offered a historical precedent within which to contextualize Ms. Caplan’s collection. We investigated the fate of private collections when they become part of an institution, either as part of a larger public collection as at the BMA, or when institutionalized as a whole, inviting comparison with additional case studies such as the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Our work with the Caplan collection enabled the students to understand how the meanings of a collection might shift as it moves from a state of ongoing flux in which its (living) owner acquires or deaccessions objects during his or her lifetime (or other periods of active collecting) to being fixed and memorialized in its entirety (and perhaps contextualized within a larger set of objects) in an institutional setting. By comparing our visits to the Caplan collection with our institutional field trip, the students could perceive more clearly how an object moves from being a marker of individual identity, and a reference point for personal memory, to a cultural sign that contributes to the establishment of an institutional identity.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Working with the archive offered by this substantive private collection (and, it must be noted, under the auspices of a collector who very openly shared her experiences and her objects with us) gave the students in this class hands-on experience engaging with art objects and with producing original writing about that art. As a professor, I can see the impact that the empirical study of a collection had on my students’ critical understanding of the practice of collecting. It gave them personalized and empathetic insight into the psychology, social function, art-historical role, and institutional impact of private collecting, allowing them to come to possess a deeper understanding of possession itself.

Virginia Anderson

Adjunct Professor, Program in Museums & Society – Johns Hopkins University

Footnotes

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Share