By

Lauren Tilton, Grace Elizabeth Hale

August 2017

¶ 1Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

This article explores how concerns about the democratization of representation and new technologies has shaped practices for collecting, organizing, preserving, interpreting, and circulating media. It outlines a participatory process of archival development informed by the emerging field of digital public humanities (DPH) and our research on the history of participatory media-making in the United States. We begin by tracing the development of Participatory Media, a digital and public project that collects and presents 1960s and 1970s film and related material. We then turn to how the project is shaped by DPH. We conclude by explaining how the history of participatory media can help DPH scholars understand both the strengths and limits of the contemporary turn toward participatory archival practices.

¶ 3Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

The Participatory Media (PM) project is a digital public humanities project that traces the history of collaborative and community-based media-making in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s and circulates the films and other forms of media created in these projects. We use the term “participatory media” to describe a set of beliefs and practices that understand media production—people’s ability to represent themselves—as both a mechanism and a measure of democratic citizenship. Inspired by political and social movements of the period and enabled by less expensive and more portable equipment, youth educators, Hollywood actors of color, grassroots organizers, and radical film and video makers sought control over media production so that silenced and marginalized communities across the United States could be seen and heard on their own terms.1 They challenged the dominance of commercial media, from feature-film studios and television networks to the emerging cable system, by developing new theories and infrastructure that members of marginalized communities could use to create their own media forms. Influenced by New Left ideas about participation as the key to remaking American politics, these new media activists argued for personal and collective access and control over content, editing, and distribution so that people could represent themselves. For them, media-making was a fundamental tool of democracy. How could people be citizens unless they could craft their own vision of their subjectivity, their place in the body politic, and their agenda for social transformation? Films and other media made through this democratic process were, in turn, a crucial marker of inclusion, proof that democracy had been achieved.

¶ 4Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

By collecting a variety of place-based projects under the rubric of participatory media, we emphasize the commonalities of collaborative media-making projects in the 1960s and 1970s across urban neighborhoods, including Puerto Rican enclaves in New York City and the African American South Side in Chicago, small towns in Appalachian Kentucky and Virginia, and remote Alaskan native settlements. We highlight ideas about self-representation, participation, and local control that link collaborative and community-based media-making to progressive social and political movements in this period. We also expose common challenges with circulation, access, and preservation that non-commercial media makers faced. Finally, we restore a mostly forgotten chapter of history, an outpouring of activist and community media production that took place between the celebrated documentary work of New Deal agencies, including the Farm Security Administration, and the more recent explosion of citizen media-making enabled by smartphones and social media.

¶ 5Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

The seeds of the project began in 2012, when Lauren Tilton won a CLIR Mellon Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources to support a year of work in documents and films related to participatory media. Because libraries and special collections have not prioritized these kinds of materials, Tilton searched for collections outside the walls of larger organizations such as universities and cultural-heritage institutions. She located people who had participated in and helped lead community film workshops in the past and gained access to their personal collections. In particular, she focused on a nationwide network of workshops that were created with funding from the Office of Equal Opportunity as part of the War on Poverty. She also communicated with and visited the few community workshops that are still in existence today, and she examined the materials that had been preserved in more traditional repositories, including the New York Public Library.

¶ 6Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Many of the past participants in community film workshops said that they had not considered the media they created worthy of archival preservation until they were contacted by scholars or by contemporary media makers who were interested in the localities represented in their work. In some cases, participants had attempted to donate their materials to archives but were deterred due to accession priorities, preservation challenges, and funding. A significant amount of materials was ruined or discarded as a result. However, some participants did hold on to materials that they generously shared with Tilton. In the process, they asked her difficult questions about long-term preservation and access. Tilton suggested digitization and public access, and many former participants agreed.

¶ 7Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

To address these problems of preservation and circulation, Tilton started the Community Film Workshop Project in the fall of 2013. Initially designed around her particular research, the project focused on aggregating information about films and streaming existing films and videos from the community film workshops. A key interlocutor, New York Public Library’s film archivist Elena Rossi-Snook, guided Tilton through the possibilities and challenges of celluloid preservation and digitization. The project quickly expanded as Tilton connected with a broad network of workshop founders and teachers, filmmakers and their families, and archivists and scholars.

¶ 8Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

In 2014, Tilton partnered with Grace Elizabeth Hale, who was researching collaborative documentary making across multiple mediums, including photography, films, community television, and audio recordings in the same time period. In the course of her own research, Hale had located scattered repositories of what she called “participatory documentary.” The Alaska Center for Documentary Film at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, for example, contained a rich collection of materials filmmakers had made in collaboration with Alaskan native villages, while scattered humanities and folklore centers across the US South had retained films and other media forms made in collaboration with rural African American and white communities. Other documentary materials had been created by grassroots political organizations fighting for civil rights, against mountaintop removal, or for union representation in the coal fields. In 2014, Tilton and Hale created the Participatory Media (PM) project to expand the scope of their individual research projects on the history of these kinds of media-making practices and their analyses of surviving films, audio recordings, and other materials.

¶ 9Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

Today, funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities public programs grant, PM has expanded into a digital, public project that interactively engages with and presents participatory media from the 1960s and 1970s. Context—the development of participatory media practices in relation to American social and cultural history in this period, US media history more broadly, and the history of America’s public documentary record—is a key part of the project’s framework. Because the media activists we study thought so deeply about the relationship between representation and power, we understand PM as a collaboration as well, moving beyond more standard methods of creating and circulating digital archives. Using new digital tools, we are producing a more participatory site. Our goal is to adapt the ideas of the media activists whose history we are constructing to the contemporary challenges of preserving and providing access to the media they produced. In other words, we strive to respect the practices and the materials by presenting and preserving participatory media in a digital project that itself invites participation online. At the intersection of public humanities and digital humanities, we found theories, methods, and strategies for presenting and sharing silenced archives and histories, as well as for thinking deeply about how participants access, collaborate, interpret, and engage with archives and collections.

¶ 11Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

PM is deeply shaped by two overlapping and rapidly changing arenas of knowledge production and circulation, digital humanities (DH) and public humanities (PH). Many practitioners have taken the big-tent approach of erring on the side of inclusion rather than exclusion when attempting to define these terms.2 We employ Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s definition of DH as “a nexus of fields within which scholars use computing technologies to investigate the kinds of questions that are traditional to the humanities” and use critical theory and other methods “to ask traditional kinds of humanities-oriented questions about computing technologies.”3

¶ 12Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

This same constellation-of-fields approach offers scholars multiple tools and methods as they struggle to define and mark the contours of the public humanities. At its core, public humanities work constructs and engages one or more publics in conversations about how people document and understand the human experience. These conversations can take multiple forms, including lectures, exhibitions, texts, oral histories, the ongoing preservation and presentation of physical sites, and the creation and maintenance of digital sites and platforms.4 Some of the most exciting projects draw on existing communities or result in community formation and civic engagement, but these conditions are not necessarily a prerequisite or outcome of PH. Practitioners of PH use theory to think about how people access, co-create, interpret, and engage humanities sources and artifacts and to develop practices that put these ideas to work in the public sphere. Increasingly, DH plays a role in PH, but it is only one aspect of a multivalent field.

¶ 13Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

At the same time, the assumption that DH is PH pervades DH discourse. The problem with this understanding is that not all PH is digital and not all DH is public. For example, neither Franco Moretti’s work on distant reading nor Matthew Jockers’ work on macroanalysis in literary studies qualifies as public humanities. Directed at specialized, academic audiences, a great deal of pioneering digital scholarship is not invested in the strangeness that Michael Warner argues is critical to the formation of a public. For Warner, the point is not that everyone must be strangers or that the arguments cannot be strange, as in unfamiliar or unsettling. Instead, in work that engages and creates publics, “reaching strangers” is the primary orientation.5 In addition to issues of audience, DH practitioners are not always concerned with core issues in the public humanities, including access, collaboration, shared authority, and translation. The big-tent metaphor is helpful to a point. However, the effective merging of DH and PH into DPH involves drawing some lines, because these decisions change how we formulate, approach, and present our objects of study.

¶ 15Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

DPH comes into formation at the intersection of DH and PH, as illustrated in Steve Lubar’s venn diagram.6 Like PH, DPH engages and often creates a public or publics for the humanities. It also employs PH concepts including shared authority, co-creation (regardless of a participant’s status as “expert” or “amateur”), and expanded audiences. Unlike PH, DPH uses DH tools and methods to do this work. It also shares with DH a fundamental commitment to scholarly and other forms of collaboration and open access.

¶ 16Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

In the last decade, a growing set of projects in the digital public humanities have emerged. Launched in 2013, the First Days Project, for example, shares the stories of immigrants’ first days in the United States. The site offers several digital interfaces, including a map, a gallery, and a timeline to add context and provide potential pathways through the collected stories. But First Days does not just make a particular archive available to users. The site also invites and enables users to share their own stories. In this way, users can also participate in making the archive and in transforming public knowledge about the experience of immigration. Another exemplary project, Histories of the National Mall, launched in 2014, offers digital support for another kind of participation, interactions with the physical landscape. This site teaches users the history of public spaces in Washington D.C. through maps; games, including scavenger hunts; and exhibitions about people and events. It is open access and optimized for mobile technology, allowing different publics to engage in this history while physically exploring the monuments, museums, lawns, paths, and gardens at the center of the nation’s capital.7

¶ 18Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

DPH is what scholars call a field in formation, an experimental set of methods and objects of study and a broad array of practitioners linked by a pervasive spirit of critical reflexivity. How, DPH scholars ask, can the digital generate new ways of collaborating, co-creating, and disseminating humanities knowledge and changing or shaping publics? While Lubar draws his Venn Diagrams with a solid line, a dotted line might better indicate how the boundaries between these fields are porous, extendible, and retractable.

¶ 19Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

In other words, we can adjust the definitions by including or excluding concepts, according to their usefulness to projects that use digital tools and methods, to create and engage publics and collaboratively develop and circulate humanities scholarship. This flexible definition allows for experimentation, play, and productive failure.

¶ 20Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

In our project, PM, experimentation, and playfulness are also conditions of the silenced histories we are trying to share. Turning to DPH methods allows for a marriage between methods, media forms, the evolving archive, and the practice of interpretation. The media producers whose 1960s and 1970s materials we seek to preserve, contextualize, and circulate experimented with media forms and participatory practices, and they worked to create and engage publics in the context of the technologies available at the time. Concerned with commercial media’s concentrated power over the circulation of knowledge, they believed the answer was to expand access to production by teaching marginalized people how to make their own films, television and radio programs, and other media forms. For them, freedom and equality meant having the right to represent yourself and your society through democratic media production as well as through the franchise. Embracing their ideas and translating them into the contemporary digital environment enables us to represent them while also restoring the history of participatory media-making. The project makes clear that earlier practitioners had an impact on intellectual and political history—their ideas about access, representation, and agency—as well as cultural history—the media they contributed to the documentary record. Scholars creating the field of DPH today have much to learn from the successes and failures of earlier experiments in creating and engaging publics by expanding access to media-making.

¶ 22Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

PM draws on methods for and theories about access, collaboration, engagement, interpretation, and participation that are central to DPH. Using cutting-edge technologies and digital tools for collaboration being developed in DPH, we are working to build a participatory site that recirculates participatory media made in the past within a structure and context sensitive to the questions about access and control that were so important to their creators. At the same time, the history and practice of participatory media informs how we practice DPH. Therefore, every stage of the project involves collaborating with people involved in the original media-making in the 1960s and 1970s in order to embed their participatory practices in the public presentation of their films and other media in the present. We argue that our project of archiving and circulating the materials and history of participatory media in the present offers one model for how archivists and scholars can collaborate with the people they are studying to co-create digital, public-humanities projects.

¶ 23Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

While we hope the project will reach a broad public, the Participatory Media project is designed to engage three target audiences—filmmakers and their communities, researchers, and contemporary participatory media makers. It has two components—a participatory digital archive and digital exhibitions. A growing area of digital humanities, digital archives employ an expansive definition of the archive as a place for collecting and preserving.8 We are using the term “archive” intentionally. As Diana Taylor argues, “The term ‘archive’ has become increasingly capacious, interchangeable with ‘save,’ ‘contain,’ ‘record,’ ‘upload,’ ‘preserve,’ and ‘share,’ and with systems of organization such as a ‘collection,’ ‘library,’ ‘inventory,’ and ‘museum.'”9 Enlarging the definitional boundaries of a term predicated on containment offers exciting opportunities to change who and how we author, define, collect, organize, preserve, and access materials. By expanding what and how we characterize a collection as an archive, we can open up questions of agency, control, and representation that the media makers we study have raised in a different historical context.10 This work in archive theory undergirds PM.

¶ 24Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

Building a digital and interpretative bridge by placing related collections in conversation, PM aggregates materials from cultural-heritage institutions, local nonprofits, individuals, and more traditional archives. Yet our project also curates a subset of media materials in order to make a series of arguments about what participatory media-making meant during the era in which it was produced. Here we follow and update for the present the shared commitments of our subjects, a range of actors including educators, grassroots organizers, and radical media makers who understood media production and circulation as tools of empowerment and social change. When the materials produced by participatory methods have been preserved and archived at all, they are held by the institutions that produced them or in collections dedicated to them in larger, more traditional repositories. This organization erases the larger, national, and at times international, conversation about access, control, and democratization of media-making within which the materials were produced. PM digitally restores this conversation by providing ways to compare films and other media made by communities including Whitesburg, Kentucky’s Appalshop, the Community Film Workshop of Chicago, New York’s Otisville Boys School, and the Alaskan Yup’ik community of Gambell on St. Lawrence Island.

¶ 25Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

Interfaces that trace themes and compare production practices across workshops, sites, and organizations will enable users to access and understand our films and other media forms. At the Time of Whaling, a film made in Gambell, Alaska, and Appalshop’s In Ya Blood, for example, both represent young people on the edge of adulthood negotiating their choices. A vampire film made by young Puerto Rican participants in a Young Filmakers Foundation (YFF) workshop and an episode of Mountain Community Television made by Appalachian youth in Norton, Virginia, both illustrate young people playing with genres of popular culture. Another common theme is how people in our featured locations think about politics and their relationships to agencies of the local, state, and federal governments. In the 1975 film On the Spring Ice, Gambell residents express a tempered gratitude toward the Coast Guard for rescuing walrus hunters stuck in offshore ice while leaving their boats, other equipment, and their catch behind. In the 1973 Appalshop film Kingdom Come School, Appalachian residents voice their concern about losing their local one-room schoolhouse to the Letcher County government’s school-consolidation project.

¶ 26Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0

In one concrete example of the kind of exploration our site will make possible, users will be able to explore how different collaborative practices shape the content and aesthetics of the media produced. At Appalshop in the late 1960s and early 1970s, local participants with limited help from outside experts taught themselves to use sixteen-millimeter film equipment and worked collectively. Appalachian residents, they believed, should document their own histories, cultural traditions, and struggles. YFF in New York City used a workshop model. Teachers trained to use sixteen-millimeter (and later eight-millimeter) equipment taught high school kids (and later elementary school kids) to make their own films. In the Alaska Native Film Project, members of the Yup’ik village of Gambell invited filmmakers Len Kamerling and Sarah Elder to help them produce films. Community members chose the stories and stars, served on the crews, and had final say about the shooting and editing done by the filmmakers. By presenting these films and other media in broader, collective frameworks, PM will enable and indeed encourage comparisons across projects that were simply not possible in the past, and produce new knowledge about the film and media history.

¶ 27Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

Overall, the goal of PM is to create a digital environment that opens up these materials to as wide a range of users as our organizations in the past served through their training and collaborative practices.11 Our digital exhibition will make arguments about the contours of participatory media in the past by embedding the streaming of films and audio within the related materials that provide historical context about key people, events, and localities. PM will feature a section for each media organization, and we are co-creating essays with the era’s participants, including Elizabeth Barrett (Appalshop) and Len Kemmerling (Alaska Native Film Project at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks), Rodger Larson (Young Filmmakers Foundation), and DeeDee Halleck (Otisville Boys Club). Through these liaisons, we are also contacting people who made films through YFF programs or Appalshop, or who wrote, starred in, or crewed films made in Gambell. The goal is to open up interpretation to those who participated. In this way, we create space in the archive for disagreements among participants about the meaning of the media produced and the strengths as well as weaknesses of the collaborative process. We trace common successes, including participants’ memories of the impact of seeing radically new images of their own under- or mis-represented communities. We also chart common problems, including the limited avenues for circulation and distribution and the difficulty of finding and reaching audiences.

¶ 28Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

Using digital technologies to enable expansive forms of contemporary participation, PM makes space for multiple interpretations and alternate meanings. As Tara Hart argues, “Archives are always reconstructive, always-already incomplete, and should never be in thrall to a singular narrative.” 12 Archiving, in other words, is an ongoing process and a social act. In the design phase, we are consulting members of the organizations and communities that produced our participatory media in the past as well as members of the potential publics the site will reach in the present. These participants, in turn, are helping us think about how users can help shape our collections and the structure of our pages and interfaces. The challenge is to build a digital archive that can remain open and in process as our users identify locations and people who appear in the films and other media, contribute additional contextual materials, provide alternative analyses of films and other media forms, and add new collections of materials. In this way, we are merging archival and digital public humanities practices in a way that updates and extends the methods of the people we are studying.

¶ 29Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

Simultaneously, our work on the history of participatory media has shaped how we practice DPH. In the 1960s and 1970s, the actors we study created new forms of media-making because they believed that democratic citizenship required not only the franchise but also a broad distribution of the skills necessary to create mass-media representations. Agency depended on the communities’ ability to represent themselves in both political and cultural terms. We are actively working to imagine what this kind of radical rethinking of democratic participation means in a digital world. In one example, we are building into our site tools that will enable users to engage in tagging and contribute to folksonomies and taxonomies. Using film and video annotation tools developed by the Media Ecology Project, users will be able to identify shots, note formal elements, add tags, and write notes, contributing to what we envision as a growing layer of additional contextual materials. These community-generated tags will form a folksonomy that augments and challenges formal taxonomies like Library of Congress Subject Headings within the project.13 We will also use these tags to build previously unrecognized connections between materials and arguments across the archive. And these new interpretations will, in turn, enable us to build new and more generous interfaces that open up the collections in ways beyond those enabled by standard search functions.

¶ 30Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0

The approach we are developing in Participatory Media has implications beyond our specific project’s approach to participation as both a practice and an ethic. Carole Palmer has called what we are trying to create “contextual mass,” “a system of interrelated sources where different types of materials and different subjects work together to support deep and multifaceted inquiry in an area of research.”14 In Palmer’s model of collection creation, scholars with their particular object of study and specialized set of materials, which are rarely in the same place, partner with archivists who hold the material, including libraries. In the Participatory Media project, we take Palmer’s model one step further, inviting people who helped create the material being archived to collaborate with both scholars and archivists in building this contextual mass and in imagining and creating new digital participatory practices for the DPH future.

For examples of work on this topic, see Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Donald Bogle, Primetime Blues: African Americans on Network Television (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015); Deirdre Boyle, Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Steven D. Classen, Watching Jim Crow: The Struggles Over Mississippi TV, 1955-1969 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Devorah Heitner, Black Power TV (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013); Chon A. Noriega, Shot in America: Television, the State, and the Rise of Chicano Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000); John McMillian, Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). [↩]

For example, hundreds of definitions were suggested during Day of DH 2014, hosted by Michigan State University. See “How do we define DH?” Day of DH 2014, http://dayofdh2014.matrix.msu.edu/members/. For more on the possibilities and limitations of the big-tent analogy, see Matthew Gold and Lauren Klein, “Digital Humanities: The Expanded Field,” Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). For an example of the use of “big tent” in conversations around public history, see Mary Rizzo, “Jon Stewart, Public Historian,” History @ Work (blog), January 13, 2013, http://ncph.org/history-at-work/jon-stewart-public-historian. [↩]

The fact that people identify as part of a particular scholarly community would disqualify them as a public, since, according to Michael Warner, “publics different from nations, races, professions, or any other group that, though not requiring copresence, saturate identity.” See Michael Warner, “Publics and Counterpublics (abbreviated version),” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88, no 4 (November 2002): 415. [↩]

Because of the tremendous growth in DPH, the National Endowment for the Humanities created a new grant called Digital Projects for the Public in 2015. [↩]

Michael Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata,” Journal of Digital Humanities 3, no. 2 (Summer 2014), http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/3-2/going-meta-on-metadata/); Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith, 1 ed., Routledge Classics (London: Routledge, 2002). [↩]

Carole Palmer, “Thematic Research Collections,” A Companion to Digital Humanities, ed. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/. [↩]

Lauren Tilton

Visiting Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities – University of Richmond

Grace Elizabeth Hale

Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History – University of Virginia

Participatory Archives

By Lauren Tilton, Grace Elizabeth Hale

August 2017

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 This article explores how concerns about the democratization of representation and new technologies has shaped practices for collecting, organizing, preserving, interpreting, and circulating media. It outlines a participatory process of archival development informed by the emerging field of digital public humanities (DPH) and our research on the history of participatory media-making in the United States. We begin by tracing the development of Participatory Media, a digital and public project that collects and presents 1960s and 1970s film and related material. We then turn to how the project is shaped by DPH. We conclude by explaining how the history of participatory media can help DPH scholars understand both the strengths and limits of the contemporary turn toward participatory archival practices.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Participatory Media: Goals and Origin

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The Participatory Media (PM) project is a digital public humanities project that traces the history of collaborative and community-based media-making in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s and circulates the films and other forms of media created in these projects. We use the term “participatory media” to describe a set of beliefs and practices that understand media production—people’s ability to represent themselves—as both a mechanism and a measure of democratic citizenship. Inspired by political and social movements of the period and enabled by less expensive and more portable equipment, youth educators, Hollywood actors of color, grassroots organizers, and radical film and video makers sought control over media production so that silenced and marginalized communities across the United States could be seen and heard on their own terms.1 They challenged the dominance of commercial media, from feature-film studios and television networks to the emerging cable system, by developing new theories and infrastructure that members of marginalized communities could use to create their own media forms. Influenced by New Left ideas about participation as the key to remaking American politics, these new media activists argued for personal and collective access and control over content, editing, and distribution so that people could represent themselves. For them, media-making was a fundamental tool of democracy. How could people be citizens unless they could craft their own vision of their subjectivity, their place in the body politic, and their agenda for social transformation? Films and other media made through this democratic process were, in turn, a crucial marker of inclusion, proof that democracy had been achieved.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 By collecting a variety of place-based projects under the rubric of participatory media, we emphasize the commonalities of collaborative media-making projects in the 1960s and 1970s across urban neighborhoods, including Puerto Rican enclaves in New York City and the African American South Side in Chicago, small towns in Appalachian Kentucky and Virginia, and remote Alaskan native settlements. We highlight ideas about self-representation, participation, and local control that link collaborative and community-based media-making to progressive social and political movements in this period. We also expose common challenges with circulation, access, and preservation that non-commercial media makers faced. Finally, we restore a mostly forgotten chapter of history, an outpouring of activist and community media production that took place between the celebrated documentary work of New Deal agencies, including the Farm Security Administration, and the more recent explosion of citizen media-making enabled by smartphones and social media.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 The seeds of the project began in 2012, when Lauren Tilton won a CLIR Mellon Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources to support a year of work in documents and films related to participatory media. Because libraries and special collections have not prioritized these kinds of materials, Tilton searched for collections outside the walls of larger organizations such as universities and cultural-heritage institutions. She located people who had participated in and helped lead community film workshops in the past and gained access to their personal collections. In particular, she focused on a nationwide network of workshops that were created with funding from the Office of Equal Opportunity as part of the War on Poverty. She also communicated with and visited the few community workshops that are still in existence today, and she examined the materials that had been preserved in more traditional repositories, including the New York Public Library.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Many of the past participants in community film workshops said that they had not considered the media they created worthy of archival preservation until they were contacted by scholars or by contemporary media makers who were interested in the localities represented in their work. In some cases, participants had attempted to donate their materials to archives but were deterred due to accession priorities, preservation challenges, and funding. A significant amount of materials was ruined or discarded as a result. However, some participants did hold on to materials that they generously shared with Tilton. In the process, they asked her difficult questions about long-term preservation and access. Tilton suggested digitization and public access, and many former participants agreed.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 To address these problems of preservation and circulation, Tilton started the Community Film Workshop Project in the fall of 2013. Initially designed around her particular research, the project focused on aggregating information about films and streaming existing films and videos from the community film workshops. A key interlocutor, New York Public Library’s film archivist Elena Rossi-Snook, guided Tilton through the possibilities and challenges of celluloid preservation and digitization. The project quickly expanded as Tilton connected with a broad network of workshop founders and teachers, filmmakers and their families, and archivists and scholars.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 In 2014, Tilton partnered with Grace Elizabeth Hale, who was researching collaborative documentary making across multiple mediums, including photography, films, community television, and audio recordings in the same time period. In the course of her own research, Hale had located scattered repositories of what she called “participatory documentary.” The Alaska Center for Documentary Film at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, for example, contained a rich collection of materials filmmakers had made in collaboration with Alaskan native villages, while scattered humanities and folklore centers across the US South had retained films and other media forms made in collaboration with rural African American and white communities. Other documentary materials had been created by grassroots political organizations fighting for civil rights, against mountaintop removal, or for union representation in the coal fields. In 2014, Tilton and Hale created the Participatory Media (PM) project to expand the scope of their individual research projects on the history of these kinds of media-making practices and their analyses of surviving films, audio recordings, and other materials.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Today, funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities public programs grant, PM has expanded into a digital, public project that interactively engages with and presents participatory media from the 1960s and 1970s. Context—the development of participatory media practices in relation to American social and cultural history in this period, US media history more broadly, and the history of America’s public documentary record—is a key part of the project’s framework. Because the media activists we study thought so deeply about the relationship between representation and power, we understand PM as a collaboration as well, moving beyond more standard methods of creating and circulating digital archives. Using new digital tools, we are producing a more participatory site. Our goal is to adapt the ideas of the media activists whose history we are constructing to the contemporary challenges of preserving and providing access to the media they produced. In other words, we strive to respect the practices and the materials by presenting and preserving participatory media in a digital project that itself invites participation online. At the intersection of public humanities and digital humanities, we found theories, methods, and strategies for presenting and sharing silenced archives and histories, as well as for thinking deeply about how participants access, collaborate, interpret, and engage with archives and collections.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

DH + PH = Digital Public Humanities (DPH)

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 PM is deeply shaped by two overlapping and rapidly changing arenas of knowledge production and circulation, digital humanities (DH) and public humanities (PH). Many practitioners have taken the big-tent approach of erring on the side of inclusion rather than exclusion when attempting to define these terms.2 We employ Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s definition of DH as “a nexus of fields within which scholars use computing technologies to investigate the kinds of questions that are traditional to the humanities” and use critical theory and other methods “to ask traditional kinds of humanities-oriented questions about computing technologies.”3

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 This same constellation-of-fields approach offers scholars multiple tools and methods as they struggle to define and mark the contours of the public humanities. At its core, public humanities work constructs and engages one or more publics in conversations about how people document and understand the human experience. These conversations can take multiple forms, including lectures, exhibitions, texts, oral histories, the ongoing preservation and presentation of physical sites, and the creation and maintenance of digital sites and platforms.4 Some of the most exciting projects draw on existing communities or result in community formation and civic engagement, but these conditions are not necessarily a prerequisite or outcome of PH. Practitioners of PH use theory to think about how people access, co-create, interpret, and engage humanities sources and artifacts and to develop practices that put these ideas to work in the public sphere. Increasingly, DH plays a role in PH, but it is only one aspect of a multivalent field.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 At the same time, the assumption that DH is PH pervades DH discourse. The problem with this understanding is that not all PH is digital and not all DH is public. For example, neither Franco Moretti’s work on distant reading nor Matthew Jockers’ work on macroanalysis in literary studies qualifies as public humanities. Directed at specialized, academic audiences, a great deal of pioneering digital scholarship is not invested in the strangeness that Michael Warner argues is critical to the formation of a public. For Warner, the point is not that everyone must be strangers or that the arguments cannot be strange, as in unfamiliar or unsettling. Instead, in work that engages and creates publics, “reaching strangers” is the primary orientation.5 In addition to issues of audience, DH practitioners are not always concerned with core issues in the public humanities, including access, collaboration, shared authority, and translation. The big-tent metaphor is helpful to a point. However, the effective merging of DH and PH into DPH involves drawing some lines, because these decisions change how we formulate, approach, and present our objects of study.

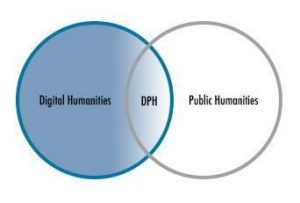

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Figure 1. Venn Diagram with solid line. Created by authors.

Figure 1. Venn Diagram with solid line. Created by authors.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 DPH comes into formation at the intersection of DH and PH, as illustrated in Steve Lubar’s venn diagram.6 Like PH, DPH engages and often creates a public or publics for the humanities. It also employs PH concepts including shared authority, co-creation (regardless of a participant’s status as “expert” or “amateur”), and expanded audiences. Unlike PH, DPH uses DH tools and methods to do this work. It also shares with DH a fundamental commitment to scholarly and other forms of collaboration and open access.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 In the last decade, a growing set of projects in the digital public humanities have emerged. Launched in 2013, the First Days Project, for example, shares the stories of immigrants’ first days in the United States. The site offers several digital interfaces, including a map, a gallery, and a timeline to add context and provide potential pathways through the collected stories. But First Days does not just make a particular archive available to users. The site also invites and enables users to share their own stories. In this way, users can also participate in making the archive and in transforming public knowledge about the experience of immigration. Another exemplary project, Histories of the National Mall, launched in 2014, offers digital support for another kind of participation, interactions with the physical landscape. This site teaches users the history of public spaces in Washington D.C. through maps; games, including scavenger hunts; and exhibitions about people and events. It is open access and optimized for mobile technology, allowing different publics to engage in this history while physically exploring the monuments, museums, lawns, paths, and gardens at the center of the nation’s capital.7

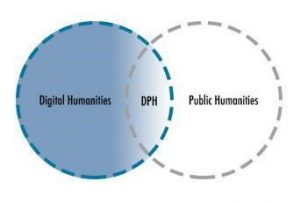

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Figure 2. Venn Diagram with dotted line. Created by authors.

Figure 2. Venn Diagram with dotted line. Created by authors.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 DPH is what scholars call a field in formation, an experimental set of methods and objects of study and a broad array of practitioners linked by a pervasive spirit of critical reflexivity. How, DPH scholars ask, can the digital generate new ways of collaborating, co-creating, and disseminating humanities knowledge and changing or shaping publics? While Lubar draws his Venn Diagrams with a solid line, a dotted line might better indicate how the boundaries between these fields are porous, extendible, and retractable.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 In other words, we can adjust the definitions by including or excluding concepts, according to their usefulness to projects that use digital tools and methods, to create and engage publics and collaboratively develop and circulate humanities scholarship. This flexible definition allows for experimentation, play, and productive failure.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 In our project, PM, experimentation, and playfulness are also conditions of the silenced histories we are trying to share. Turning to DPH methods allows for a marriage between methods, media forms, the evolving archive, and the practice of interpretation. The media producers whose 1960s and 1970s materials we seek to preserve, contextualize, and circulate experimented with media forms and participatory practices, and they worked to create and engage publics in the context of the technologies available at the time. Concerned with commercial media’s concentrated power over the circulation of knowledge, they believed the answer was to expand access to production by teaching marginalized people how to make their own films, television and radio programs, and other media forms. For them, freedom and equality meant having the right to represent yourself and your society through democratic media production as well as through the franchise. Embracing their ideas and translating them into the contemporary digital environment enables us to represent them while also restoring the history of participatory media-making. The project makes clear that earlier practitioners had an impact on intellectual and political history—their ideas about access, representation, and agency—as well as cultural history—the media they contributed to the documentary record. Scholars creating the field of DPH today have much to learn from the successes and failures of earlier experiments in creating and engaging publics by expanding access to media-making.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

Participatory Media as Digital Public Humanities

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 PM draws on methods for and theories about access, collaboration, engagement, interpretation, and participation that are central to DPH. Using cutting-edge technologies and digital tools for collaboration being developed in DPH, we are working to build a participatory site that recirculates participatory media made in the past within a structure and context sensitive to the questions about access and control that were so important to their creators. At the same time, the history and practice of participatory media informs how we practice DPH. Therefore, every stage of the project involves collaborating with people involved in the original media-making in the 1960s and 1970s in order to embed their participatory practices in the public presentation of their films and other media in the present. We argue that our project of archiving and circulating the materials and history of participatory media in the present offers one model for how archivists and scholars can collaborate with the people they are studying to co-create digital, public-humanities projects.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 While we hope the project will reach a broad public, the Participatory Media project is designed to engage three target audiences—filmmakers and their communities, researchers, and contemporary participatory media makers. It has two components—a participatory digital archive and digital exhibitions. A growing area of digital humanities, digital archives employ an expansive definition of the archive as a place for collecting and preserving.8 We are using the term “archive” intentionally. As Diana Taylor argues, “The term ‘archive’ has become increasingly capacious, interchangeable with ‘save,’ ‘contain,’ ‘record,’ ‘upload,’ ‘preserve,’ and ‘share,’ and with systems of organization such as a ‘collection,’ ‘library,’ ‘inventory,’ and ‘museum.'”9 Enlarging the definitional boundaries of a term predicated on containment offers exciting opportunities to change who and how we author, define, collect, organize, preserve, and access materials. By expanding what and how we characterize a collection as an archive, we can open up questions of agency, control, and representation that the media makers we study have raised in a different historical context.10 This work in archive theory undergirds PM.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Building a digital and interpretative bridge by placing related collections in conversation, PM aggregates materials from cultural-heritage institutions, local nonprofits, individuals, and more traditional archives. Yet our project also curates a subset of media materials in order to make a series of arguments about what participatory media-making meant during the era in which it was produced. Here we follow and update for the present the shared commitments of our subjects, a range of actors including educators, grassroots organizers, and radical media makers who understood media production and circulation as tools of empowerment and social change. When the materials produced by participatory methods have been preserved and archived at all, they are held by the institutions that produced them or in collections dedicated to them in larger, more traditional repositories. This organization erases the larger, national, and at times international, conversation about access, control, and democratization of media-making within which the materials were produced. PM digitally restores this conversation by providing ways to compare films and other media made by communities including Whitesburg, Kentucky’s Appalshop, the Community Film Workshop of Chicago, New York’s Otisville Boys School, and the Alaskan Yup’ik community of Gambell on St. Lawrence Island.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Interfaces that trace themes and compare production practices across workshops, sites, and organizations will enable users to access and understand our films and other media forms. At the Time of Whaling, a film made in Gambell, Alaska, and Appalshop’s In Ya Blood, for example, both represent young people on the edge of adulthood negotiating their choices. A vampire film made by young Puerto Rican participants in a Young Filmakers Foundation (YFF) workshop and an episode of Mountain Community Television made by Appalachian youth in Norton, Virginia, both illustrate young people playing with genres of popular culture. Another common theme is how people in our featured locations think about politics and their relationships to agencies of the local, state, and federal governments. In the 1975 film On the Spring Ice, Gambell residents express a tempered gratitude toward the Coast Guard for rescuing walrus hunters stuck in offshore ice while leaving their boats, other equipment, and their catch behind. In the 1973 Appalshop film Kingdom Come School, Appalachian residents voice their concern about losing their local one-room schoolhouse to the Letcher County government’s school-consolidation project.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 In one concrete example of the kind of exploration our site will make possible, users will be able to explore how different collaborative practices shape the content and aesthetics of the media produced. At Appalshop in the late 1960s and early 1970s, local participants with limited help from outside experts taught themselves to use sixteen-millimeter film equipment and worked collectively. Appalachian residents, they believed, should document their own histories, cultural traditions, and struggles. YFF in New York City used a workshop model. Teachers trained to use sixteen-millimeter (and later eight-millimeter) equipment taught high school kids (and later elementary school kids) to make their own films. In the Alaska Native Film Project, members of the Yup’ik village of Gambell invited filmmakers Len Kamerling and Sarah Elder to help them produce films. Community members chose the stories and stars, served on the crews, and had final say about the shooting and editing done by the filmmakers. By presenting these films and other media in broader, collective frameworks, PM will enable and indeed encourage comparisons across projects that were simply not possible in the past, and produce new knowledge about the film and media history.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Overall, the goal of PM is to create a digital environment that opens up these materials to as wide a range of users as our organizations in the past served through their training and collaborative practices.11 Our digital exhibition will make arguments about the contours of participatory media in the past by embedding the streaming of films and audio within the related materials that provide historical context about key people, events, and localities. PM will feature a section for each media organization, and we are co-creating essays with the era’s participants, including Elizabeth Barrett (Appalshop) and Len Kemmerling (Alaska Native Film Project at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks), Rodger Larson (Young Filmmakers Foundation), and DeeDee Halleck (Otisville Boys Club). Through these liaisons, we are also contacting people who made films through YFF programs or Appalshop, or who wrote, starred in, or crewed films made in Gambell. The goal is to open up interpretation to those who participated. In this way, we create space in the archive for disagreements among participants about the meaning of the media produced and the strengths as well as weaknesses of the collaborative process. We trace common successes, including participants’ memories of the impact of seeing radically new images of their own under- or mis-represented communities. We also chart common problems, including the limited avenues for circulation and distribution and the difficulty of finding and reaching audiences.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 Using digital technologies to enable expansive forms of contemporary participation, PM makes space for multiple interpretations and alternate meanings. As Tara Hart argues, “Archives are always reconstructive, always-already incomplete, and should never be in thrall to a singular narrative.” 12 Archiving, in other words, is an ongoing process and a social act. In the design phase, we are consulting members of the organizations and communities that produced our participatory media in the past as well as members of the potential publics the site will reach in the present. These participants, in turn, are helping us think about how users can help shape our collections and the structure of our pages and interfaces. The challenge is to build a digital archive that can remain open and in process as our users identify locations and people who appear in the films and other media, contribute additional contextual materials, provide alternative analyses of films and other media forms, and add new collections of materials. In this way, we are merging archival and digital public humanities practices in a way that updates and extends the methods of the people we are studying.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 Simultaneously, our work on the history of participatory media has shaped how we practice DPH. In the 1960s and 1970s, the actors we study created new forms of media-making because they believed that democratic citizenship required not only the franchise but also a broad distribution of the skills necessary to create mass-media representations. Agency depended on the communities’ ability to represent themselves in both political and cultural terms. We are actively working to imagine what this kind of radical rethinking of democratic participation means in a digital world. In one example, we are building into our site tools that will enable users to engage in tagging and contribute to folksonomies and taxonomies. Using film and video annotation tools developed by the Media Ecology Project, users will be able to identify shots, note formal elements, add tags, and write notes, contributing to what we envision as a growing layer of additional contextual materials. These community-generated tags will form a folksonomy that augments and challenges formal taxonomies like Library of Congress Subject Headings within the project.13 We will also use these tags to build previously unrecognized connections between materials and arguments across the archive. And these new interpretations will, in turn, enable us to build new and more generous interfaces that open up the collections in ways beyond those enabled by standard search functions.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 The approach we are developing in Participatory Media has implications beyond our specific project’s approach to participation as both a practice and an ethic. Carole Palmer has called what we are trying to create “contextual mass,” “a system of interrelated sources where different types of materials and different subjects work together to support deep and multifaceted inquiry in an area of research.”14 In Palmer’s model of collection creation, scholars with their particular object of study and specialized set of materials, which are rarely in the same place, partner with archivists who hold the material, including libraries. In the Participatory Media project, we take Palmer’s model one step further, inviting people who helped create the material being archived to collaborate with both scholars and archivists in building this contextual mass and in imagining and creating new digital participatory practices for the DPH future.

Lauren Tilton

Visiting Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities – University of Richmond

Grace Elizabeth Hale

Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History – University of Virginia

Footnotes

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Share