¶ 2Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Religious institutions occupied the heart of emerging polities in medieval India,1 where they functioned as the primary loci of community building. The remains that survive from these sites preserve a valuable, tangible record of a lived past, a “material archive” that offers access to facets of human life that are otherwise inaccessible. Temples function as institutions for the preservation of knowledge, sites of memory where one may encounter the voices of myriad individuals and groups who sought to inscribe themselves upon these spaces across generations. While the mention of an archive may typically evoke an image of stacks of papers, records (or what are now digital) files, the temple deals in alternative sources: inscriptions, images, architectural fragments, and the spatial articulation and arrangement of monuments in the physical landscape. While the spatial limits of a temple site are relatively fixed, the challenge to the researcher is to understand how the, often overwhelming and seemingly disorganized, materials housed within this circumscribed site relate to each other—in other words, to identify particular collections within the archive.

¶ 3Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0

Visiting the site or remains of a medieval temple in contemporary India is to experience the setting as it is presented to us, not as it was. Since scholars are typically attentive only to those particular objects or monuments needed to support their historiography, the question of presentation does not figure in the existing literature on these places.2 Unexplored are the ways in which collecting and curatorial practices—undertaken at both the official (i.e. government sanctioned) and local level—determine the organization, display, and accessibility of materials and, in so doing, condition the production of historical knowledge. This study charts a new direction. It explores the collecting practices that lend these archives their unique texture, and shows how these practices are informed by the primary ways in which the sites are apprehended and valued: as monuments, lived spaces, and patrimony.

¶ 4Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0Figure 1. Mount Harṣa, Sikar District, Rajasthan, India. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

¶ 5Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0Figure 2. Close view of the Mount Harṣa temple complex along the ridgeline. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

¶ 14Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

To illustrate the ways in which these valuations of the site shape collections in practice and on the ground, I use the tenth-century temple complex at Harṣagiri (the “Mountain of Joy”) in northeast Rajasthan as an example of a material archive. This site—comprised of multiple shrines extending across the mountain ridgeline—is one of the richest yet least understood of North India’s medieval religious centers (Figures 1 and 2). Heaped in courtyards, repurposed in structures, locked in storerooms, and dispersed throughout surrounding temples and museums, the extensive remains from the site are overwhelming and their arrangement appears haphazard (Figures 3, 4, and 5).3 This situation is not unique to Harṣa, but characteristic of many medieval sites. The inscrutability and inaccessibility of the collections is problematic insofar as it renders invisible material sources that are critical for the study of the Indian past. This discussion works to determine the syntax of the site as it is encountered today, by parsing the curatorial practices that have informed its current organization. Exploring the implementation and effects of preservation practices on the collections from Harṣagiri is not only instructive for scholars of medieval Indian history; addressing a largely unrecognized and untheorized collection, this brief study aims to open a broader dialogue about using material archives to study the past.

¶ 15Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0Figure 3. Architectural fragments, images, and dressed stones surround the foundation of the c. tenth-century liṅga shrine on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 19Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0Figure 5. Small sculptures that once adorned a medieval shrine plastered in a wall of a residential structure on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 21Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

Medieval temple remains are physical reminders of historical events, the socio-cultural realia that provide a basis for understanding the social world of this pivotal historical period. It is only by studying the collections from a site in as much detail as possible that its chronological layers can be ascertained and, with them, the voices of particular cultural agents and communities who engaged with the site. This “micro-level” investigation of a particular locale then opens up to broader questions about the role of a particular place in a regional landscape and the social location of the people who used it. For scholars investigating these archives, the issues of access to and preservation of sources is critical.

¶ 22Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0

Scholarly engagement with these sites as historical sources is intimately connected with the imperatives of preservation introduced by nineteenth-century colonial archeologists, who regarded the temples as valuable monuments. I use monument here in a specific way—to evoke not only a sense of massive physical dimensions, but historical magnitude as well.4 The preservation of this material heritage was seen as crucial due to the common misconception that India was devoid of any textual history.5 In the words of Alexander Cunningham, considered the father of Indian archeology, writing in 1861:

¶ 23Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

During the one hundred years of British domination in India, the Government had done little or nothing towards the preservation of its ancient monuments, which, in the total absence of any written history, form the only reliable source of information as to the early condition of the country…. Some of these monuments … are daily suffering from the effects of time, and … must soon disappear altogether, unless preserved by the accurate drawings and faithful descriptions of the archeologist.6

¶ 24Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

The value of a monument, and the objects housed within it, was contingent upon its integrity as a reflection of a particular historical moment. According to the early archeological hierarchy of value, objects and structures of greatest antiquity held the most value and, as such, had to be protected and preserved. One of the most significant implications of this valuation of the temple was the introduction of the State and District Archeological Museums. The social function of these institutions as a medium of colonial control has been explored in detail.7 As it pertains to the temple-as-archive, the advent of the museum reflects a particular logic of collection and curation, whereby objects deemed historically significant were removed from their structural contexts for safekeeping. This isolating of particular materials delimited separate collections that can be challenging to situate within the larger archive. In most cases, objects are identified according to the site or the state district in which they were found, but details regarding their particular structural contexts are not provided. This is true, for example, in this arrangement of architectural fragments from the area surrounding Mt. Harṣa displayed in the garden of the Government Museum in Sikar (Figure 6).

¶ 25Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0Figure 6. Architectural fragments of c. tenth century on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 26Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0

The curatorial practices that are informed by the valuation of the temple as monument operate alongside alternative conceptions of the space.8 For the majority of Indians who visit Harsagiri today, the monument is not their experience. Instead, the temple as a lived space is primary. Temples under active worship enshrine material embodiments of deities, and their use is governed in large part by the rituals and other activities required to honor the presence of that deity. The spaces are functional, largely public, and adapted to suit the needs and devotional repertoires of the communities that use them. The contemporary use of medieval temple spaces by religious communities exhibits significant parallels with their social function in previous centuries. Dedicatory inscriptions show that investments in sanctified spaces were often framed in soteriological terms; the donor and her family members, living and deceased, accrued religious “merit” through these acts of piety. Equally important is that investments in temple complexes were not necessarily individual undertakings, nor were donations singular acts. Temples were dynamic parts of equally dynamic religious landscapes that provided potential for merit making long after their foundations were laid.

¶ 27Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

As institutions intended to last “as long as the sun and the moon should endure,” according to a common epigraphic trope, religious institutions required regular maintenance, and temple complexes were periodically augmented and renovated. These renovations were funded through various means—pious donations as well as taxes on trade goods, tithes, and revenues from real estate and agrarian land-holdings. While a foundation inscription may name an individual donor, the task of maintaining a living temple required a collaborative effort. Collective or corporate giving by trading diasporas, artisans, and guilds created tangible links to places where community identities and connections could be expressed and renewed. Evidence of this commitment to community-based and collaborative temple maintenance is easily observed at Mount Harṣa (and these practices are discussed in detail in the following pages). Yet, in this case, the renovation practices and aesthetics typically do not conform with the archeological aesthetics of preservation that inspired the early interventions characterized above (Figures 7 and 8). The concern for historical continuity is not keenly felt. Structural materials and images from multiple shrines within the same temple complex may be combined and repurposed in a kind of bricolage that creates additional collections within the archive (Figures 9 and 10). For the contemporary community using the temples on Mt. Harṣa, the museification of space runs counter to the conception of history that informs their engagement with material culture, which is akin to the Sanskrit word purāṇa—that is, something rooted in the primordial past, yet accessible in the present, renewable, able to be made and re-made without a loss of integrity.9

¶ 30Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0Figure 8. Medieval images and fragments rebuilt in the exterior retaining wall of the modern Bhairava temple (see Figure 7).

¶ 52Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0

To round out this monument/lived space binary, temple sites in contemporary India now serve a third function as patrimony. These places are staged and strategically manipulated to substantiate a particular vision of a national past that citizens should protect and value as a “cultural asset.”10 Upon entering the confines of the many medieval temples now designated as protected monuments by the Archeological Survey of India (ASI), visitors are greeted by signboards with the exhortation to “sustain your heritage and feel glorious” or the reminder that “our heritage is our glory” (Figure 11).11 As a potent symbol of the past, a temple under the purview of the ASI is idealized as a static entity, the integrity of which depends on its preservation as something unchanging and fundamentally removed from the vicissitudes of the present. Temples are surrounded by gated, and often locked, enclosures, where resident caretakers are employed to guard storerooms where sculptures have been safely locked away. Often, the grounds are meticulously landscaped, and strolling the quiet gardens encourages a meditative or reflective mood.12 Additional placards of rules posted at entryways prohibit ritual practices and social gatherings. While there is a certain resonance between the valuation of medieval temple sites as monument and patrimony, the notion of patrimony also places an economic value on these sites as evinced by the locking away of objects and images deemed particularly significant. If we follow the official logic, storing materials in locked cellars and storerooms protects them from theft and the black-market antiquities trade. At the same time, the perception of these sites as a kind of national treasury has occasioned a mode of collecting that establishes hidden collections within the larger temple archive.

¶ 53Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0Figure 11. An ASI signboard reading “Sustain your Heritage and Feel Glorious” marks the ascent to Mt. Harṣa.

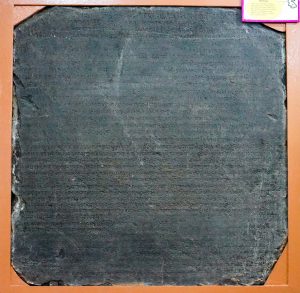

¶ 55Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0Figure 12. Tenth-century Harṣa Stone Inscription on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 56Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0

The parameters of the temple complex on Mt. Harsa are determined, on the one hand, geographically. The area of religious and building activity occupies a plateau on the southwest end of the mountain. ASI renovations have included a low fence that further circumscribes the built area. Yet, as the valuation of the site as monument defines, the materials that have informed scholarly understanding of the site are not all located on the mountain. Some deemed most significant were removed to State and District Archeological Museums. One of these objects—the one that has received the most scholarly attention to date—is a tenth-century stone inscription (Figure 12). The massive slab of black stone measures approximately three square feet and records a lengthy eulogy composed of thirty-seven lines of Sanskrit poetry.13

¶ 57Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

The purpose of the inscription was to testify to the enduring connection between the Cāhamānas, a localized ruling clan, and the god Śiva who, eulogized as the Lord Harṣa (Joy), was credited as the source of the clan’s success. As declared in Verse 27 of the inscription, “This row of great kings had the origin of their virtues in devotion to Śambhu [Śiva]. The holy Harṣa is their family deity; through him the family has become illustrious.”14

¶ 58Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0

The epithet “Harṣa” refers to the localized manifestation of the God, the tutelary deity of the eponymous mountain that dominates the surrounding landscape. Situated near their ancestral homeland, Mt. Harṣa served as the ideal place for the rulers to celebrate their political status.15 According to the inscription, Śiva as Harṣa was manifest in the mountaintop temple in the form of a liṅga (the phallic emblem of Śiva that served as a focus of ritual and devotional activity in medieval Indian temples, as today) (Figure 13).16

¶ 60Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0

He [Śiva]—who, full of joy (harṣa) after he incinerated the enemies of the gods at Tripura with his burning arrow (and) was worshipped by a multitude of joyful gods led by Indra, who praised and bowed to him—took up residence here on the mountain peak under the very name Harṣa out of favor for Bhārata [India]. May that moon-crested one, now with a second residence, dwell (here) in the form of the liṅga for your well-being. (Verse 7)

¶ 61Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0

According to the earliest reports, the inscribed stone was found in the rubble surrounding the remains of a massive medieval temple. Since the epigraph credits the Cāhamāna ruler, Siṃharāja, with renovating a monumental temple to honor his family’s lineage deity, today this shrine is regarded as the old Cāhamāna temple, the same structure referred to in the inscription. Together, the temple and the stone inscription served as a highly visible manifestation of the family’s political ambitions.17

¶ 62Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

To date, the Harṣa inscription has been read primarily as a source for Rajasthan’s dynastic history and the temple conceived as a royal cult center. This decontextualized reading results, in large part, from the isolation of the inscribed stone from the other materials within the temple archive, a practice of collecting intended to preserve the history of the monument. In fact, both the inscription and the temple site it commemorates preserve traces of the combined efforts of multiple social networks; religious specialists, mercantile communities, and lay devotees all invested in this place. These acts of commemoration were not restricted to textual expressions. The atmosphere of joy and celebration is materialized in sculpture from the site itself, examples of which are preserved within the complex and in the District Archeological Museum in the nearby town of Sikar. Depictions of joyful devotion, dance, and music provide one of the dominant themes of the iconographic program (Figure 14). These images also reflect the multivocality of the larger Śaiva community through the variety of people shown worshipping the Lord; religious specialists, ascetics, and members of the lay community are depicted engaged in the quintessential Śaiva practice of venerating the liṅga (Figures 15 and 16).

¶ 63Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0Figure 14. Sculpted fragment from Mt. Harṣa showing a dancing Śiva surrounded by musicians, District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 64Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0Figure 15. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing an ascetic venerating a liṅga.

¶ 65Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0Figure 16. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing a lay couple venerating a liṅga with a religious specialist presiding.

¶ 76Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0

During my fieldwork at Harṣagiri, I also noted the remains of at least twelve temple foundations (c. tenth to eleventh century). Some of these foundations are significantly smaller than the Cāhamāna shrine, which could indicate that they were dedications by non-elite donors and serve as further evidence for the wide range of social participation on this sacred mountain—that is, to its life as a lived space (Figure 17).18 In this way, the built landscape similarly reinforces the investment of these various groups in participating and celebrating the sanctity of Lord Śiva’s abode.

¶ 79Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0

Although the Harṣa inscription clearly styles the mountain as a Śaiva space, this preference on the part of the rulers does not imply that Śiva was the only deity enshrined on the Harṣagiri. The temple dedicated to the Cāhamāna’s patron deity was one of many in an extensive complex, and the material record preserves evidence of Śaivism alongside a broader and widely dispersed set of religious practices and concerns. Despite the richness of the sources, there has not yet been an effort to map patterns in the iconographic program across the site; to identify communities using the spaces; or to explore the relationships between the various structures that comprise the complex. These significant lacunae in the scholarship on Harṣagiri can be attributed to several factors, not least of which is its geographically remote location. Practical and logistical issues aside, the expanse of the site and the sheer number of sculptures and architectural fragments piled and repurposed throughout the complex is overwhelming, even after multiple visits. By considering the typology outlined above, we may better understand the logic of the site and discern distinct collections with the temple archive. Rather than attempting to isolate a particular historical layer in a monumental history, considering the function of the complex as a lived space and as patrimony provides additional insight into the organizational strategies that govern this material archive.

¶ 80Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0

The stone inscription discussed above serves as the only “finding aid,” albeit with a very selective scope. Since the rhetorical aim of this source was to praise the Cāhamāna’s temple and homologize the mountain with Śiva, the poet does not explicitly mention the worship of other deities within the sanctified space. Considering the ASI-protected sculptures together with the other site materials permits a more nuanced perspective of religious life at the site. Judging from iconographic remains, some of the smaller temple foundations mentioned earlier would have been dedicated to Viṣṇu, one of the major deities of the Hindu pantheon and Śiva’s primary competitor. During my fieldwork, I identified three displaced temple lintels deposited within courtyards at the site in which Viṣṇu appears as the central deity (Figure 17). The central position of this deity—easily recognized by his signature attributes of club (gaḍā) and discus (cakra)—is a strong indication that the shrines these lintels framed were dedicated to Viṣṇu. While the ruling elites aligned themselves closely with Śiva, the smaller Vaiṣṇava structures attest to the broad-based support of other cults within the shared space of the temple complex. Other notable icons of specific manifestations (āvatāras) of Viṣṇu are preserved around the site. The presence of these images is striking, as it points to the activities of artisans and donors with a detailed knowledge of Viṣṇu’s mythology and theology.

¶ 81Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0

In addition to these examples, the most interesting evidence of Vaiṣṇava activity is recorded within the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine. Given that this temple was originally a Śaiva dedication, we would expect an image of Śiva or one of his manifestations in the central niche of the lintel. Yet, it is Viṣṇu who now occupies this prominent place (Figure 18). The temple is still under active worship as a Śiva temple, but as a result of ongoing renovations and repairs, a portion of a Viṣṇu temple has been repurposed within the Śiva shrine. For the devotees who continue to use the space, this does not present an incongruity. The benefits of visiting the temple and worshipping the deity are not compromised by the current status of the temple as a kind of medieval bricolage (Figure 19).

¶ 93Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0

Parsing the collections requires access not only to materials scattered throughout the courtyards, but to two locked storerooms as well. In keeping with the construction of the site as patrimony, the ASI maintains storage areas where the best-preserved sculptures and fragments are kept. Access to these collections requires special written permission from the District Officer in Jaipur. But even with the required documents, one is not guaranteed to see the materials. On my first visit the paperwork was accepted, but the only person with keys to the storerooms was mysteriously (or perhaps conveniently) absent. It was not until my third visit that he had returned. The “tale of the missing key” is a common trope and it represents a strategy for restricting access to those materials deemed most valuable by the government officers. Since very few scholars have the opportunity to visit Harṣa, and even fewer have the time to return on multiple occasions, such practices effectively render these ASI collections invisible.

¶ 94Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0

On my most recent visit in January 2016, I discovered that one of the ASI storerooms contains an extremely rare image of Chāyā (Shadow), one of the two wives of the sun god, Sūrya (Figure 20). Chāyā’s iconography bears a strong resemblance to that of her husband. She is depicted holding a lotus flower in each hand. The horses that draw the chariot of the Sun are shown at her feet. In addition to these attributes that convey her association with Sūrya, Chāyā also holds a trident in one of her left hands. As the signature attribute of Śiva, the inclusion of the trident expresses a visual link between Chāyā and Śiva. The intervisibility of Śiva and Sūrya at Harṣa is also historically significant. The Sikar museum collection includes icons that blend key iconographic features of these deities to produce “composite” forms. When seen as objects from a coherent collection, the Chāyā icon, composite images, and the Sūrya sculptures repurposed in the temple complex provide a clear indication that Mt. Harṣa was a regionally prominent center for the Sun cult.

¶ 111Leave a comment on paragraph 111 0

Having considered the inclusion of competing religious cults with the Harṣa complex, there are also many deities included within the Śaiva pantheon that occupied important places within the site. The most prominent and widely worshipped of these was the Goddess in her various manifestations: as Śiva’s wife Pārvatī, the demon-slaying Durgā, or the fearsome Cāmuṇḍa with her necklace of skulls. In addition to the Goddess par excellence as embodied in Pārvatī, Harṣa’s sanctified spaces abound in representations of the various subordinate, yet still powerful, goddesses sometimes associated with her, i.e. mātṛkas (Mother goddesses) and yoginīs (Figure 21). These ambivalent goddesses were seen as sources of power that were worshipped by religious adepts and connected with fertility cults, invoked for the protection of expectant mothers and young children. At present, nearly all the images of these goddesses are rebuilt in walls and under worship in small shrines within a circular open-roofed structure on the eastern end of the complex (Figure 22). The original purpose and date of the structure are impossible to determine; its architectural layers preserve numerous historical moments and building phases. Yet, it is significant to note that the building recalls the structure of early yoginī shrines, which typically enshrined sixty-four goddesses in a circular temple that was open to the sky. Ritual activity at this place today is centered on an underground temple to Bhairava, a particularly fearsome manifestation of Śiva who is propitiated by couples to ensure the protection of their children (Figure 23). It is likely that the contemporary use of this area and its association with the goddesses preserve echoes of a much earlier and enduring association of this place with the Mothers and the yoginīs.

¶ 114Leave a comment on paragraph 114 0Figure 23. Resident priest seated in the Bhairava shrine with medieval sculptures rebuilt in the wall behind.

¶ 115Leave a comment on paragraph 115 0

In light of the numerous images of Viṣṇu, Sūrya, and the Goddess preserved at Harṣa, monumental sculptures of Śiva himself are conspicuous in their absence. No significant images are housed on site, and those taken to the Sikar museum are part of architectural fragments suited to adorn external temple niches, but not to serve as the primary image under worship in the temple. The only icon I have found that fits this latter description is now on display at the State Archeological Museum in Ajmer. The remarkable image depicts a four-faced (caturmukha) Śiva liṇga, with the major deities of the Hindu pantheon—Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Sūrya, and Śiva—positioned around the base (Figure 24). This iconic representation of Śiva and arrangement of deities in a single sculpture is rare. Given that the central image is the liṅga, it materializes a Śaiva theology. At the same time, the presence of the other deities encircling the base suggests an inclusive religious vision whereby these deities are incorporated within the Śaiva religious hierarchy.19 Considering this displaced sculpture as part of the larger material archive, an important resonance between visual and spatial expressions of religious hierarchy at Mt. Harṣa is evident. The position of Śiva at the center of the monumental liṅga echoes the articulation of shrines on Mt. Harṣa. The dominance of Śiva was established by locating the liṅga shrine at the center of the complex, where it served as the primary focal point around which the other smaller shrines dedicated to other deities were clustered.

¶ 117Leave a comment on paragraph 117 0

The presence of these other temples prompts the further observation that religious hierarchy and authority were not necessarily expressed through strategies of exclusion. The dispersion of temples and images attests to a richly varied and complex religious center, one that would have accommodated a range of ritual concerns and practices. Since this multivocality is not given expression in the epigraphic record, it is only through analysis of the collections on site that these voices may be heard.

¶ 120Leave a comment on paragraph 120 0

This work was supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) under the Mellon Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) under the Mellon International Dissertation Research Fellowship.

Debates regarding historic periodization in pre-modern India are too extensive to rehearse here. I use “medieval” to designate the period between the ninth and thirteenth centuries CE. [↩]

Deborah Stein has explored local practices of preservation in a recent article. Her focus is primarily on the debates over aesthetics that divide government-sponsored and locally funded restoration projects. Deborah Stein, “To Curate in the Field: Archaeological Privatization and the Aesthetic Legislation of Antiquity in India,” Contemporary South Asia 19, no. 1 (2011): 25–47. Padma Kaimal has addressed the dispersal of sculptures from the Kanchi temple complex in Tamil Nadu to museums. Padma Kaimal, Scattered Goddesses: Travels with the Yoginis (Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 2012). [↩]

All of the photographs included in this article were taken by the author during fieldwork. [↩]

John Guillory’s opposition of monuments and documents and Aleida Assman’s juxtaposition of canon and archive have informed my understanding and specific use of the term “monument.” See John Guillory, “Monuments and Documents: Panofsky on the Object of Study in the Humanities,” History of Humanities 1, no. 1 (2016): 9–30; Aleida Assman, “Canon and Archive,” in A Companion to Cultural Memory Studies, ed. Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nunning (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2000), 97–108. [↩]

Much has been written about this presumed lack of written history, and it is summarized succinctly by James Fitzgerald in his work on Indian narrative historiography. James Fitzgerald, “History and Primordium in Ancient Indian Historical Writing: Itihāsa and Purāṇa in the Mahābhārata and Beyond,” in Thinking, Recording, and Writing History in the Ancient World, First Edition, ed. Kurt A. Raaflaub (West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 41–60. [↩]

Cunningham’s Memo to the General Lord Canning. Reprinted in Preface to Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65, vol. 1, Archeological Survey of India (Simla: Government Central Press, 1871), iii. [↩]

Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India (New York: Colombia University Press, 2000). [↩]

For today, just as in the early nineteenth century when colonial archeologists first began restoring Indian monuments, the task of preservation has also implied safeguarding places from the local communities who continue to engage them as active centers of social and religious life. In their reports, colonial officers of the ASI also documented their frustration as they struggled to maintain the ancient temples in such a way that could preserve the “aesthetic of ruin,” but prevent them from actually falling down. In their efforts to realize this goal, the officers found themselves constantly at odds with local communities, whose efforts at temple repair were characterized as amateurish or misguided at best and, at their worst, downright destructive. The ASI was tasked not only with overseeing new renovation projects, but also correcting previous works undertaken by local communities or temple trusts, and stopping destructive works in progress. For example, reporting on the renovation work to temples at Māṇḍu, where “things had got into a muddle” in the absence of proper supervision, Henry Cousens wrote, “What strikes one at first, on looking at the repairs, is the disagreeable raw newness of the work. New, fresh, pink sandstone and white, dead, unpolished marble contrast violently with the old blackened walls and domes.… [T]he work is calculated to provoke very unfavorable criticism.” Annual Progress Report of the Archeological Survey of India, Western Circle (Delhi: 1905), 15. [↩]

Fitzgerald, “History and Primordium in Ancient Indian Historical Writing.” [↩]

Eric Ketelaar, “Muniments and Monuments: The Dawn of the Archive as Cultural Patrimony,” Journal of Archeological Science 7 (2007): 343–47. In previous discussions of state manipulation of temple spaces, I have described this practice as “heritage making.” Considering Ketelaar’s distinction between “heritage” and “patrimony,” I now think the latter is a more apt term to describe this nationalistic shaping of the past. [↩]

These signboards are printed in English and in Hindi. The Hindi word virāsat is translated as “heritage.” Following upon n. 10, I think the semantics of this term align most closely with patrimony. Like patrimony, virāsat refers to an inheritance or hereditary birthright. [↩]

On archeological landscapes and the idea of the picturesque in colonial India, see Guha-Thakurta, Monuments, Objects, Histories, 3–42. [↩]

The inscription itself comprises forty lines, but the final three are in prose. [↩]

[mahā ]rājāvalī cāsau śambhubhaktiguṇodayā / śrī harṣaḥ kuladevo ‘ syās tasmād divyaḥ kulakramaḥ //27//

(Anuṣṭubh)

Translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The Sanskrit text is reproduced from Kielhorn’s edition. [↩]

The inscription has been edited three times: E. Dean, Journal of the Asiatic Societyof Bengal IV (1835): 361-400; F. Kielhorn, Epigraphia Indica 2 (1894): 116-140; D.R. Bhandarkar, The Indian Antiquary, XLII (1913). As Kielhorn reports, the inscription was discovered by G.E. Rankin and E. Dean in 1834. It measures approximately three square feet and is carved on black stone (116). Their reports were published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal IV (1835): 361–400. The inscription is now housed in the Sikar Government Museum. There are, in fact, three dates recorded in the inscription: 1) VS 1013/956 CE, the date at which the temple constructed by Allaṭa was reportedly completed; 2) VS 1027/970 CE, the date of Allaṭa’s death; and 3) VS 1030/973 CE, the concluding date for subsequent donations made to the temple after its completion. [↩]

nūnaṃ vāṇāgnidagdhattripurasuraripu[r jā]taharṣaḥ saharṣair indrādyair devavṛndaiḥ kṛtanutinatibhiḥ pūjyamāno ‘ttra śaile / yo ‘bhūn nāmnāpi harṣo giriśikharabhuvor bhāratānugrahāya sa stād vo liṅgarūpo dviguṇitabhavanaś candramauliḥ śivāya // 7// (Sragdharā) [↩]

The medieval visitor’s experience of the sanctified space would have been shaped significantly by the rulers’ efforts to express their political ambitions. Stone inscriptions, like the temples to which they were typically affixed, evoked power, substance, and permanence. As characterized by Tamara Sears, these objects “functioned as new instantiations into the physical environment, which carried the potential to significantly transform both the meaning and experience of encountering a physical place.” Tamara Sears, Worldly Gurus and Spiritual Kings (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014) 46–48. [↩]

The editors of the Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture also note the smaller shrines, which they take to be roughly contemporaneous with the main temple. They also confirm that the uneven arrangement and size of the smaller sub-shrines means it was not originally conceived as a unified group-of-temples complex. Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture vol. 2, pt. 2, North India: Period of Early Maturity c. AD 700-900 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 107. [↩]

There is one other important image from Harṣa on display in Ajmer that materializes a similar hierarchical, yet ultimately inclusive vision. The image, called a liṅgodhavamūrti, represents an important event in Śaiva mythology in which Śiva manifests himself to Viṣṇu and Brahmā as a fiery and endless liṅga of light. The two gods are confounded by Śiva’s infinite power and forced to admit his supremacy. [↩]

Elizabeth A. Cecil

Post-Doctoral Researcher – International Institute of Asian StudiesLecturer, Institute for Area Studies – Leiden University,

The Medieval Temple as Material Archive: Historical Preservation and the Production of Knowledge at Mount Harṣa

By Elizabeth A. Cecil

August 2017

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Introduction

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Religious institutions occupied the heart of emerging polities in medieval India,1 where they functioned as the primary loci of community building. The remains that survive from these sites preserve a valuable, tangible record of a lived past, a “material archive” that offers access to facets of human life that are otherwise inaccessible. Temples function as institutions for the preservation of knowledge, sites of memory where one may encounter the voices of myriad individuals and groups who sought to inscribe themselves upon these spaces across generations. While the mention of an archive may typically evoke an image of stacks of papers, records (or what are now digital) files, the temple deals in alternative sources: inscriptions, images, architectural fragments, and the spatial articulation and arrangement of monuments in the physical landscape. While the spatial limits of a temple site are relatively fixed, the challenge to the researcher is to understand how the, often overwhelming and seemingly disorganized, materials housed within this circumscribed site relate to each other—in other words, to identify particular collections within the archive.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Visiting the site or remains of a medieval temple in contemporary India is to experience the setting as it is presented to us, not as it was. Since scholars are typically attentive only to those particular objects or monuments needed to support their historiography, the question of presentation does not figure in the existing literature on these places.2 Unexplored are the ways in which collecting and curatorial practices—undertaken at both the official (i.e. government sanctioned) and local level—determine the organization, display, and accessibility of materials and, in so doing, condition the production of historical knowledge. This study charts a new direction. It explores the collecting practices that lend these archives their unique texture, and shows how these practices are informed by the primary ways in which the sites are apprehended and valued: as monuments, lived spaces, and patrimony.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Figure 1. Mount Harṣa, Sikar District, Rajasthan, India. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Figure 1. Mount Harṣa, Sikar District, Rajasthan, India. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Figure 2. Close view of the Mount Harṣa temple complex along the ridgeline. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Figure 2. Close view of the Mount Harṣa temple complex along the ridgeline. Satellite Image courtesy of Google Earth.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 To illustrate the ways in which these valuations of the site shape collections in practice and on the ground, I use the tenth-century temple complex at Harṣagiri (the “Mountain of Joy”) in northeast Rajasthan as an example of a material archive. This site—comprised of multiple shrines extending across the mountain ridgeline—is one of the richest yet least understood of North India’s medieval religious centers (Figures 1 and 2). Heaped in courtyards, repurposed in structures, locked in storerooms, and dispersed throughout surrounding temples and museums, the extensive remains from the site are overwhelming and their arrangement appears haphazard (Figures 3, 4, and 5).3 This situation is not unique to Harṣa, but characteristic of many medieval sites. The inscrutability and inaccessibility of the collections is problematic insofar as it renders invisible material sources that are critical for the study of the Indian past. This discussion works to determine the syntax of the site as it is encountered today, by parsing the curatorial practices that have informed its current organization. Exploring the implementation and effects of preservation practices on the collections from Harṣagiri is not only instructive for scholars of medieval Indian history; addressing a largely unrecognized and untheorized collection, this brief study aims to open a broader dialogue about using material archives to study the past.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Figure 3. Architectural fragments, images, and dressed stones surround the foundation of the c. tenth-century liṅga shrine on Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 3. Architectural fragments, images, and dressed stones surround the foundation of the c. tenth-century liṅga shrine on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Figure 4. Carved pillars repurposed in a residential structure on Mt. Harṣa

Figure 4. Carved pillars repurposed in a residential structure on Mt. Harṣa

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Figure 5. Small sculptures that once adorned a medieval shrine plastered in a wall of a residential structure on Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 5. Small sculptures that once adorned a medieval shrine plastered in a wall of a residential structure on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Valuing the Past: Monument, Lived Space, and Patrimony

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Medieval temple remains are physical reminders of historical events, the socio-cultural realia that provide a basis for understanding the social world of this pivotal historical period. It is only by studying the collections from a site in as much detail as possible that its chronological layers can be ascertained and, with them, the voices of particular cultural agents and communities who engaged with the site. This “micro-level” investigation of a particular locale then opens up to broader questions about the role of a particular place in a regional landscape and the social location of the people who used it. For scholars investigating these archives, the issues of access to and preservation of sources is critical.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Scholarly engagement with these sites as historical sources is intimately connected with the imperatives of preservation introduced by nineteenth-century colonial archeologists, who regarded the temples as valuable monuments. I use monument here in a specific way—to evoke not only a sense of massive physical dimensions, but historical magnitude as well.4 The preservation of this material heritage was seen as crucial due to the common misconception that India was devoid of any textual history.5 In the words of Alexander Cunningham, considered the father of Indian archeology, writing in 1861:

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 During the one hundred years of British domination in India, the Government had done little or nothing towards the preservation of its ancient monuments, which, in the total absence of any written history, form the only reliable source of information as to the early condition of the country…. Some of these monuments … are daily suffering from the effects of time, and … must soon disappear altogether, unless preserved by the accurate drawings and faithful descriptions of the archeologist.6

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 The value of a monument, and the objects housed within it, was contingent upon its integrity as a reflection of a particular historical moment. According to the early archeological hierarchy of value, objects and structures of greatest antiquity held the most value and, as such, had to be protected and preserved. One of the most significant implications of this valuation of the temple was the introduction of the State and District Archeological Museums. The social function of these institutions as a medium of colonial control has been explored in detail.7 As it pertains to the temple-as-archive, the advent of the museum reflects a particular logic of collection and curation, whereby objects deemed historically significant were removed from their structural contexts for safekeeping. This isolating of particular materials delimited separate collections that can be challenging to situate within the larger archive. In most cases, objects are identified according to the site or the state district in which they were found, but details regarding their particular structural contexts are not provided. This is true, for example, in this arrangement of architectural fragments from the area surrounding Mt. Harṣa displayed in the garden of the Government Museum in Sikar (Figure 6).

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Figure 6. Architectural fragments of c. tenth century on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

Figure 6. Architectural fragments of c. tenth century on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 The curatorial practices that are informed by the valuation of the temple as monument operate alongside alternative conceptions of the space.8 For the majority of Indians who visit Harsagiri today, the monument is not their experience. Instead, the temple as a lived space is primary. Temples under active worship enshrine material embodiments of deities, and their use is governed in large part by the rituals and other activities required to honor the presence of that deity. The spaces are functional, largely public, and adapted to suit the needs and devotional repertoires of the communities that use them. The contemporary use of medieval temple spaces by religious communities exhibits significant parallels with their social function in previous centuries. Dedicatory inscriptions show that investments in sanctified spaces were often framed in soteriological terms; the donor and her family members, living and deceased, accrued religious “merit” through these acts of piety. Equally important is that investments in temple complexes were not necessarily individual undertakings, nor were donations singular acts. Temples were dynamic parts of equally dynamic religious landscapes that provided potential for merit making long after their foundations were laid.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 As institutions intended to last “as long as the sun and the moon should endure,” according to a common epigraphic trope, religious institutions required regular maintenance, and temple complexes were periodically augmented and renovated. These renovations were funded through various means—pious donations as well as taxes on trade goods, tithes, and revenues from real estate and agrarian land-holdings. While a foundation inscription may name an individual donor, the task of maintaining a living temple required a collaborative effort. Collective or corporate giving by trading diasporas, artisans, and guilds created tangible links to places where community identities and connections could be expressed and renewed. Evidence of this commitment to community-based and collaborative temple maintenance is easily observed at Mount Harṣa (and these practices are discussed in detail in the following pages). Yet, in this case, the renovation practices and aesthetics typically do not conform with the archeological aesthetics of preservation that inspired the early interventions characterized above (Figures 7 and 8). The concern for historical continuity is not keenly felt. Structural materials and images from multiple shrines within the same temple complex may be combined and repurposed in a kind of bricolage that creates additional collections within the archive (Figures 9 and 10). For the contemporary community using the temples on Mt. Harṣa, the museification of space runs counter to the conception of history that informs their engagement with material culture, which is akin to the Sanskrit word purāṇa—that is, something rooted in the primordial past, yet accessible in the present, renewable, able to be made and re-made without a loss of integrity.9

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 Figure 7. Medieval temple of Harṣanātha (foreground) with modern Bhairava temple (background).

Figure 7. Medieval temple of Harṣanātha (foreground) with modern Bhairava temple (background).

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 Figure 8. Medieval images and fragments rebuilt in the exterior retaining wall of the modern Bhairava temple (see Figure 7).

Figure 8. Medieval images and fragments rebuilt in the exterior retaining wall of the modern Bhairava temple (see Figure 7).

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Figure 9. Temple fragments repurposed as votive cairns within the temple compound, Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 9. Temple fragments repurposed as votive cairns within the temple compound, Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Figure 10. Medieval sculpture under active worship.

Figure 10. Medieval sculpture under active worship.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 To round out this monument/lived space binary, temple sites in contemporary India now serve a third function as patrimony. These places are staged and strategically manipulated to substantiate a particular vision of a national past that citizens should protect and value as a “cultural asset.”10 Upon entering the confines of the many medieval temples now designated as protected monuments by the Archeological Survey of India (ASI), visitors are greeted by signboards with the exhortation to “sustain your heritage and feel glorious” or the reminder that “our heritage is our glory” (Figure 11).11 As a potent symbol of the past, a temple under the purview of the ASI is idealized as a static entity, the integrity of which depends on its preservation as something unchanging and fundamentally removed from the vicissitudes of the present. Temples are surrounded by gated, and often locked, enclosures, where resident caretakers are employed to guard storerooms where sculptures have been safely locked away. Often, the grounds are meticulously landscaped, and strolling the quiet gardens encourages a meditative or reflective mood.12 Additional placards of rules posted at entryways prohibit ritual practices and social gatherings. While there is a certain resonance between the valuation of medieval temple sites as monument and patrimony, the notion of patrimony also places an economic value on these sites as evinced by the locking away of objects and images deemed particularly significant. If we follow the official logic, storing materials in locked cellars and storerooms protects them from theft and the black-market antiquities trade. At the same time, the perception of these sites as a kind of national treasury has occasioned a mode of collecting that establishes hidden collections within the larger temple archive.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Figure 11. An ASI signboard reading “Sustain your Heritage and Feel Glorious” marks the ascent to Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 11. An ASI signboard reading “Sustain your Heritage and Feel Glorious” marks the ascent to Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 Celebrating Śiva on the “Mountain of Joy”

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 Figure 12. Tenth-century Harṣa Stone Inscription on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

Figure 12. Tenth-century Harṣa Stone Inscription on display at the District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 The parameters of the temple complex on Mt. Harsa are determined, on the one hand, geographically. The area of religious and building activity occupies a plateau on the southwest end of the mountain. ASI renovations have included a low fence that further circumscribes the built area. Yet, as the valuation of the site as monument defines, the materials that have informed scholarly understanding of the site are not all located on the mountain. Some deemed most significant were removed to State and District Archeological Museums. One of these objects—the one that has received the most scholarly attention to date—is a tenth-century stone inscription (Figure 12). The massive slab of black stone measures approximately three square feet and records a lengthy eulogy composed of thirty-seven lines of Sanskrit poetry.13

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 The purpose of the inscription was to testify to the enduring connection between the Cāhamānas, a localized ruling clan, and the god Śiva who, eulogized as the Lord Harṣa (Joy), was credited as the source of the clan’s success. As declared in Verse 27 of the inscription, “This row of great kings had the origin of their virtues in devotion to Śambhu [Śiva]. The holy Harṣa is their family deity; through him the family has become illustrious.”14

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 The epithet “Harṣa” refers to the localized manifestation of the God, the tutelary deity of the eponymous mountain that dominates the surrounding landscape. Situated near their ancestral homeland, Mt. Harṣa served as the ideal place for the rulers to celebrate their political status.15 According to the inscription, Śiva as Harṣa was manifest in the mountaintop temple in the form of a liṅga (the phallic emblem of Śiva that served as a focus of ritual and devotional activity in medieval Indian temples, as today) (Figure 13).16

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Figure 13. Four-faced (caturmukha) liṅga under worship in the medieval temple on Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 13. Four-faced (caturmukha) liṅga under worship in the medieval temple on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 He [Śiva]—who, full of joy (harṣa) after he incinerated the enemies of the gods at Tripura with his burning arrow (and) was worshipped by a multitude of joyful gods led by Indra, who praised and bowed to him—took up residence here on the mountain peak under the very name Harṣa out of favor for Bhārata [India]. May that moon-crested one, now with a second residence, dwell (here) in the form of the liṅga for your well-being. (Verse 7)

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 According to the earliest reports, the inscribed stone was found in the rubble surrounding the remains of a massive medieval temple. Since the epigraph credits the Cāhamāna ruler, Siṃharāja, with renovating a monumental temple to honor his family’s lineage deity, today this shrine is regarded as the old Cāhamāna temple, the same structure referred to in the inscription. Together, the temple and the stone inscription served as a highly visible manifestation of the family’s political ambitions.17

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 To date, the Harṣa inscription has been read primarily as a source for Rajasthan’s dynastic history and the temple conceived as a royal cult center. This decontextualized reading results, in large part, from the isolation of the inscribed stone from the other materials within the temple archive, a practice of collecting intended to preserve the history of the monument. In fact, both the inscription and the temple site it commemorates preserve traces of the combined efforts of multiple social networks; religious specialists, mercantile communities, and lay devotees all invested in this place. These acts of commemoration were not restricted to textual expressions. The atmosphere of joy and celebration is materialized in sculpture from the site itself, examples of which are preserved within the complex and in the District Archeological Museum in the nearby town of Sikar. Depictions of joyful devotion, dance, and music provide one of the dominant themes of the iconographic program (Figure 14). These images also reflect the multivocality of the larger Śaiva community through the variety of people shown worshipping the Lord; religious specialists, ascetics, and members of the lay community are depicted engaged in the quintessential Śaiva practice of venerating the liṅga (Figures 15 and 16).

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Figure 14. Sculpted fragment from Mt. Harṣa showing a dancing Śiva surrounded by musicians, District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

Figure 14. Sculpted fragment from Mt. Harṣa showing a dancing Śiva surrounded by musicians, District Archeological Museum, Sikar, Rajasthan.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 Figure 15. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing an ascetic venerating a liṅga.

Figure 15. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing an ascetic venerating a liṅga.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 Figure 16. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing a lay couple venerating a liṅga with a religious specialist presiding.

Figure 16. Sculpted panel on a pillar inside the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine showing a lay couple venerating a liṅga with a religious specialist presiding.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 During my fieldwork at Harṣagiri, I also noted the remains of at least twelve temple foundations (c. tenth to eleventh century). Some of these foundations are significantly smaller than the Cāhamāna shrine, which could indicate that they were dedications by non-elite donors and serve as further evidence for the wide range of social participation on this sacred mountain—that is, to its life as a lived space (Figure 17).18 In this way, the built landscape similarly reinforces the investment of these various groups in participating and celebrating the sanctity of Lord Śiva’s abode.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 Figure 17. Sculpted lintel with Viṣṇu in the central niche.

Figure 17. Sculpted lintel with Viṣṇu in the central niche.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 Identifying Collections on Site

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 Although the Harṣa inscription clearly styles the mountain as a Śaiva space, this preference on the part of the rulers does not imply that Śiva was the only deity enshrined on the Harṣagiri. The temple dedicated to the Cāhamāna’s patron deity was one of many in an extensive complex, and the material record preserves evidence of Śaivism alongside a broader and widely dispersed set of religious practices and concerns. Despite the richness of the sources, there has not yet been an effort to map patterns in the iconographic program across the site; to identify communities using the spaces; or to explore the relationships between the various structures that comprise the complex. These significant lacunae in the scholarship on Harṣagiri can be attributed to several factors, not least of which is its geographically remote location. Practical and logistical issues aside, the expanse of the site and the sheer number of sculptures and architectural fragments piled and repurposed throughout the complex is overwhelming, even after multiple visits. By considering the typology outlined above, we may better understand the logic of the site and discern distinct collections with the temple archive. Rather than attempting to isolate a particular historical layer in a monumental history, considering the function of the complex as a lived space and as patrimony provides additional insight into the organizational strategies that govern this material archive.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 The stone inscription discussed above serves as the only “finding aid,” albeit with a very selective scope. Since the rhetorical aim of this source was to praise the Cāhamāna’s temple and homologize the mountain with Śiva, the poet does not explicitly mention the worship of other deities within the sanctified space. Considering the ASI-protected sculptures together with the other site materials permits a more nuanced perspective of religious life at the site. Judging from iconographic remains, some of the smaller temple foundations mentioned earlier would have been dedicated to Viṣṇu, one of the major deities of the Hindu pantheon and Śiva’s primary competitor. During my fieldwork, I identified three displaced temple lintels deposited within courtyards at the site in which Viṣṇu appears as the central deity (Figure 17). The central position of this deity—easily recognized by his signature attributes of club (gaḍā) and discus (cakra)—is a strong indication that the shrines these lintels framed were dedicated to Viṣṇu. While the ruling elites aligned themselves closely with Śiva, the smaller Vaiṣṇava structures attest to the broad-based support of other cults within the shared space of the temple complex. Other notable icons of specific manifestations (āvatāras) of Viṣṇu are preserved around the site. The presence of these images is striking, as it points to the activities of artisans and donors with a detailed knowledge of Viṣṇu’s mythology and theology.

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 In addition to these examples, the most interesting evidence of Vaiṣṇava activity is recorded within the Mt. Harṣa liṅga shrine. Given that this temple was originally a Śaiva dedication, we would expect an image of Śiva or one of his manifestations in the central niche of the lintel. Yet, it is Viṣṇu who now occupies this prominent place (Figure 18). The temple is still under active worship as a Śiva temple, but as a result of ongoing renovations and repairs, a portion of a Viṣṇu temple has been repurposed within the Śiva shrine. For the devotees who continue to use the space, this does not present an incongruity. The benefits of visiting the temple and worshipping the deity are not compromised by the current status of the temple as a kind of medieval bricolage (Figure 19).

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 Figure 18. Sculpted lintel with Viṣṇu in the central niche rebuilt in the medieval liṅga temple.

Figure 18. Sculpted lintel with Viṣṇu in the central niche rebuilt in the medieval liṅga temple.

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 Figure 19. Devotees worshipping the liṅga shrine with the trident of Śiva displayed in the foreground.

Figure 19. Devotees worshipping the liṅga shrine with the trident of Śiva displayed in the foreground.

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0 Parsing the collections requires access not only to materials scattered throughout the courtyards, but to two locked storerooms as well. In keeping with the construction of the site as patrimony, the ASI maintains storage areas where the best-preserved sculptures and fragments are kept. Access to these collections requires special written permission from the District Officer in Jaipur. But even with the required documents, one is not guaranteed to see the materials. On my first visit the paperwork was accepted, but the only person with keys to the storerooms was mysteriously (or perhaps conveniently) absent. It was not until my third visit that he had returned. The “tale of the missing key” is a common trope and it represents a strategy for restricting access to those materials deemed most valuable by the government officers. Since very few scholars have the opportunity to visit Harṣa, and even fewer have the time to return on multiple occasions, such practices effectively render these ASI collections invisible.

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 On my most recent visit in January 2016, I discovered that one of the ASI storerooms contains an extremely rare image of Chāyā (Shadow), one of the two wives of the sun god, Sūrya (Figure 20). Chāyā’s iconography bears a strong resemblance to that of her husband. She is depicted holding a lotus flower in each hand. The horses that draw the chariot of the Sun are shown at her feet. In addition to these attributes that convey her association with Sūrya, Chāyā also holds a trident in one of her left hands. As the signature attribute of Śiva, the inclusion of the trident expresses a visual link between Chāyā and Śiva. The intervisibility of Śiva and Sūrya at Harṣa is also historically significant. The Sikar museum collection includes icons that blend key iconographic features of these deities to produce “composite” forms. When seen as objects from a coherent collection, the Chāyā icon, composite images, and the Sūrya sculptures repurposed in the temple complex provide a clear indication that Mt. Harṣa was a regionally prominent center for the Sun cult.

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 Figure 20. Image of Chāyā held in one of the ASI storerooms on Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 20. Image of Chāyā held in one of the ASI storerooms on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0 Figure 21. Two fragmentary goddess images (c. tenth century) rebuilt in a small shrine.

Figure 21. Two fragmentary goddess images (c. tenth century) rebuilt in a small shrine.

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0

¶ 98 Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0

¶ 99 Leave a comment on paragraph 99 0

¶ 100 Leave a comment on paragraph 100 0

¶ 101 Leave a comment on paragraph 101 0

¶ 102 Leave a comment on paragraph 102 0

¶ 103 Leave a comment on paragraph 103 0

¶ 104 Leave a comment on paragraph 104 0

¶ 105 Leave a comment on paragraph 105 0

¶ 106 Leave a comment on paragraph 106 0

¶ 107 Leave a comment on paragraph 107 0

¶ 108 Leave a comment on paragraph 108 0

¶ 109 Leave a comment on paragraph 109 0

¶ 110 Leave a comment on paragraph 110 0

¶ 111 Leave a comment on paragraph 111 0 Having considered the inclusion of competing religious cults with the Harṣa complex, there are also many deities included within the Śaiva pantheon that occupied important places within the site. The most prominent and widely worshipped of these was the Goddess in her various manifestations: as Śiva’s wife Pārvatī, the demon-slaying Durgā, or the fearsome Cāmuṇḍa with her necklace of skulls. In addition to the Goddess par excellence as embodied in Pārvatī, Harṣa’s sanctified spaces abound in representations of the various subordinate, yet still powerful, goddesses sometimes associated with her, i.e. mātṛkas (Mother goddesses) and yoginīs (Figure 21). These ambivalent goddesses were seen as sources of power that were worshipped by religious adepts and connected with fertility cults, invoked for the protection of expectant mothers and young children. At present, nearly all the images of these goddesses are rebuilt in walls and under worship in small shrines within a circular open-roofed structure on the eastern end of the complex (Figure 22). The original purpose and date of the structure are impossible to determine; its architectural layers preserve numerous historical moments and building phases. Yet, it is significant to note that the building recalls the structure of early yoginī shrines, which typically enshrined sixty-four goddesses in a circular temple that was open to the sky. Ritual activity at this place today is centered on an underground temple to Bhairava, a particularly fearsome manifestation of Śiva who is propitiated by couples to ensure the protection of their children (Figure 23). It is likely that the contemporary use of this area and its association with the goddesses preserve echoes of a much earlier and enduring association of this place with the Mothers and the yoginīs.

¶ 112 Leave a comment on paragraph 112 0 Figure 22. View of the circular open-roof structure housing the Bhairava shrine on Mt. Harṣa.

Figure 22. View of the circular open-roof structure housing the Bhairava shrine on Mt. Harṣa.

¶ 113 Leave a comment on paragraph 113 0

¶ 114 Leave a comment on paragraph 114 0 Figure 23. Resident priest seated in the Bhairava shrine with medieval sculptures rebuilt in the wall behind.

Figure 23. Resident priest seated in the Bhairava shrine with medieval sculptures rebuilt in the wall behind.

¶ 115 Leave a comment on paragraph 115 0 In light of the numerous images of Viṣṇu, Sūrya, and the Goddess preserved at Harṣa, monumental sculptures of Śiva himself are conspicuous in their absence. No significant images are housed on site, and those taken to the Sikar museum are part of architectural fragments suited to adorn external temple niches, but not to serve as the primary image under worship in the temple. The only icon I have found that fits this latter description is now on display at the State Archeological Museum in Ajmer. The remarkable image depicts a four-faced (caturmukha) Śiva liṇga, with the major deities of the Hindu pantheon—Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Sūrya, and Śiva—positioned around the base (Figure 24). This iconic representation of Śiva and arrangement of deities in a single sculpture is rare. Given that the central image is the liṅga, it materializes a Śaiva theology. At the same time, the presence of the other deities encircling the base suggests an inclusive religious vision whereby these deities are incorporated within the Śaiva religious hierarchy.19 Considering this displaced sculpture as part of the larger material archive, an important resonance between visual and spatial expressions of religious hierarchy at Mt. Harṣa is evident. The position of Śiva at the center of the monumental liṅga echoes the articulation of shrines on Mt. Harṣa. The dominance of Śiva was established by locating the liṅga shrine at the center of the complex, where it served as the primary focal point around which the other smaller shrines dedicated to other deities were clustered.

¶ 116 Leave a comment on paragraph 116 0 Figure 24. Monumental caturmukha liṅga from Mt. Harṣa, State Archeological Museum, Ajmer, Rajasthan.

Figure 24. Monumental caturmukha liṅga from Mt. Harṣa, State Archeological Museum, Ajmer, Rajasthan.

¶ 117 Leave a comment on paragraph 117 0 The presence of these other temples prompts the further observation that religious hierarchy and authority were not necessarily expressed through strategies of exclusion. The dispersion of temples and images attests to a richly varied and complex religious center, one that would have accommodated a range of ritual concerns and practices. Since this multivocality is not given expression in the epigraphic record, it is only through analysis of the collections on site that these voices may be heard.

¶ 118 Leave a comment on paragraph 118 0

¶ 119 Leave a comment on paragraph 119 0 Acknowledgements

¶ 120 Leave a comment on paragraph 120 0 This work was supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) under the Mellon Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources and the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) under the Mellon International Dissertation Research Fellowship.

¶ 121 Leave a comment on paragraph 121 0

śrī harṣaḥ kuladevo ‘ syās tasmād divyaḥ kulakramaḥ //27//

(Anuṣṭubh)

Translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The Sanskrit text is reproduced from Kielhorn’s edition. [↩]

indrādyair devavṛndaiḥ kṛtanutinatibhiḥ pūjyamāno ‘ttra śaile /

yo ‘bhūn nāmnāpi harṣo giriśikharabhuvor bhāratānugrahāya

sa stād vo liṅgarūpo dviguṇitabhavanaś candramauliḥ śivāya // 7//

(Sragdharā) [↩]

Elizabeth A. Cecil

Post-Doctoral Researcher – International Institute of Asian StudiesLecturer, Institute for Area Studies – Leiden University,

Footnotes

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Share